Chapter 1

The Public Purpose Requirement

by Kara A. Millonzi

Introduction

The North Carolina Constitution is the foundation of our state’s government. Among other things, it establishes the state legislature (General Assembly) and authorizes it to create, and define the powers of, local government entities. Specifically, Section 1 of Article VII states as follows:

The constitution also sets certain limitations on the legislature’s authority. Some of those limitations provide protections for citizens against government intrusion and coercion. Others guarantee rights to citizens. And some limitations prohibit certain government actions or impose process requirements as a condition of certain government undertakings. Among these limitations are several that relate directly or indirectly to local government finance. They include

-

uniformity of property tax rate (art. V, § 2(2));

-

prohibition against contracting away taxing authority (art. V, § 2(1));

-

authorization for special taxing districts (art. V, § 2(4));

-

limitations on property-tax exclusions and exemptions (art. V, § 2(2));

-

requirement to distribute clear proceeds of certain fines, penalties, and forfeitures to public schools (art. IX, § 7);

-

public-school funding mandate (art. IX, § 2; art. I, § 15);

-

limitations on authorizing debt financing (art. V, § 4(1));

-

requirement for voter approval to pledge full faith and credit as security for debt (art. V, § 4(2));

-

prohibition against loaning or aiding government credit without general law authority and voter approval (art. V, § 4(3));

-

authorization for project-development financing (art. V, § 14);

-

prohibition against expending public funds except by authority of law (art. V, § 7(2));

-

authorization for government entities to contract with private entities to accomplish public purposes (art. V, § 2(7));

-

prohibition against exclusive privileges or emoluments (art. I, § 32).

Some of these provisions apply directly to local governments. The rest are limitations on the legislature’s grants of authority to local governments. Regardless, local officials always must interpret their statutory grants of authority in a manner that is consistent with constitutional requirements. It is thus important for local government officials to have a general understanding of the relevant constitutional provisions.

Most of the constitutional provisions related to local government finance are discussed in other chapters in this text. This chapter introduces the fundamental constitutional limitation on local government finance—the public purpose clause.

Defining Public Purpose

Section 2(1) of Article V of the North Carolina Constitution provides that the “power of taxation shall be exercised in a just and equitable manner, for public purposes only, and shall never be surrendered, suspended, or contracted away.”

Known as the public purpose clause, this provision requires that all public funds, no matter their source, be expended for the benefit of the citizens of a unit generally and not solely for the benefit of particular persons or interests. According to the North Carolina Supreme Court, “[a]lthough the constitutional language speaks to the ‘power of taxation,’ the limitation has not been confined to government use of tax revenues.” The public purpose clause is better understood as a limitation on government expenditures. In other words, a government entity may not make an expenditure of public funds that does not serve a public purpose.

The constitution does not define the phrase “public purpose.” We must discern its meaning through (ever-evolving) legislative enactments and judicial interpretations. “The initial responsibility for determining what is and what is not a public purpose rests with the legislature. . . . ” North Carolina courts have been deferential to legislative declarations that an authorized undertaking serves a public purpose but have not considered them to be determinative. The state supreme court has set forth two guiding principles to analyze whether a government activity satisfies the constitutional requirement. First, the activity must “involve[] a reasonable connection with the convenience and necessity” of the particular unit of government. Second, the “activity [must] benefit[] the public generally, as opposed to special interests or persons. . . . ”

A close review of the case law reveals that there are actually three parts to the inquiry. For one, the expenditure has to be for an appropriate government activity. For another, the expenditure has to provide a primary benefit to the government’s citizens/constituents. Finally, the expenditure also has to benefit the public generally, not just a few private individuals or entities.

Appropriate Government Activity

When we think of appropriate government activities, certain functions usually come to mind—police and fire protection, street construction and maintenance, public health programs, utilities, parks and recreation. North Carolina courts routinely have held that these, and similar traditional government functions, serve a public purpose. But to constitute an appropriate government activity for a particular local government, the local government must have statutory authority to engage in the activity. This authority is granted by the General Assembly through general laws, local acts, and charter provisions. If a local government does not have statutory authority for a particular purpose, that purpose is not an appropriate government activity for that local unit. According to the North Carolina Supreme Court,

Thus, in analyzing public purpose, a threshold question is whether or not there is statutory authority for the proposed expenditure. As a practical matter, for most undertakings this is the only inquiry that counts. If there is clear statutory authority to engage in an activity and a public official acts within that authority, it is likely that the activity constitutes a public purpose. As noted above, courts are deferential to the legislature’s determination that an undertaking satisfies the public purpose clause. Most of the authority granted to counties is found in Chapter 153A of the North Carolina General Statutes (hereinafter G.S.), although there are various additional provisions sprinkled throughout several other chapters. Similarly, G.S. Chapter 160A prescribes most, but not all, authority applicable to municipalities. Public authorities must look to their various enabling statutes to determine the contours of their powers and authorities.

There are some activities, however, that the General Assembly may not grant authority to local governments to undertake. These activities are not appropriate for government action and should instead be reserved for the private sector. Determining this division between public and private is often difficult, though. As the state supreme court repeatedly has explained,

The courts, thus, have sometimes held that “new” activities that are perceived as outgrowths of more-traditional government functions serve a public purpose. “Whether an activity is within the appropriate scope of governmental involvement and is reasonably related to communal needs may be evaluated by determining how similar the activity is to others which this Court has held to be within the permissible realm of governmental action.” In Martin v. North Carolina Housing Corp., the state supreme court held that government funding of low-income residential housing served a public purpose. In so holding, the court tied the government’s concern for safe and sanitary housing for its citizens to its traditional role of combating slum conditions. Similarly, in Madison Cablevision, Inc. v. City of Morganton, the court held that the municipal provision of cable television services served a public purpose because such services were a natural outgrowth of the types of communications facilities that local governments had been operating for many years, including auditoriums, libraries, fairs, public radio stations, and public television stations. In Maready v. City of Winston-Salem, the court acknowledged that the “importance of contemporary circumstances in assessing the public purpose of governmental endeavors highlights the essential fluidity of the concept.” In that case, the court upheld a variety of economic-development incentive payments against a public purpose challenge.

In a few cases, the courts have found that an activity is neither a traditional government activity nor an outgrowth of a traditional government activity and, consequently, that the activity does not serve a public purpose. In Nash v. Tarboro, the court held that it was not a public purpose for a town to issue general obligation bonds in order to construct and operate a hotel, finding that, at least at the time, owning and operating a hotel was purely a private business with no connection to traditional government activities. (Although the case has not been overturned, it is possible that a court would not rule the same way today, reflecting the fact that what constitutes a public purpose evolves over time.)

And, occasionally, courts have determined that activities that appear to be natural extensions of traditional government activities, nonetheless, do not satisfy the public purpose clause. In Foster v. North Carolina Medical Care Commission, the court held that the expenditure of public funds to finance the construction of a hospital facility that was to be privately operated, managed, and controlled did not serve a public purpose even though the “primary purpose” of a “privately owned hospital is the same as that of a publicly owned hospital.” In 1971, the legislature had enacted the North Carolina Medical Care Commission Hospital Facilities Finance Act, which established a commission and authorized it to issue revenue bonds to finance the construction of public and private hospital facilities. The Council of State had allotted $15,000 to the commission from the state’s contingency fund to implement the revenue bond program. It was this allocation that the court found violated the public purpose clause. The state’s authority to expend tax funds to construct and operate a public hospital did not extend to expending funds to subsidize a privately owned hospital, even if both were providing the same type of public benefits. According to the court, “[m]any objects may be public in the general sense that their attainment will confer a public benefit or promote the public convenience but not be public in the sense that the taxing power of the State may be used to accomplish them.” Thus, a court must look not only at the ends sought, but also at the means used to accomplish a public purpose.

Note, however, that the constitution was amended after Foster to specifically authorize the state legislature to enact laws to allow a government entity to “contract with and appropriate money to any person, association, or corporation for the accomplishment of public purposes only.” The legislature subsequently provided broad authority for general-purpose local governments—counties and municipalities—to contract with a private entity to perform any activity in which the local unit has statutory authority to engage. This authority allows a local government to contract with a private entity to act as an agent of the government in performing the specific function. The local government must undertake certain oversight functions to ensure that the private entity carries out the public purpose. This issue is further explored in the last section of this chapter, addressing funding for nonprofits and other private entities.

Benefits the Government’s Citizens or Constituents

In addition to being for an appropriate government activity, an expenditure of public funds must benefit the citizens or constituents of the government entity that is engaging in the activity. That is, the primary benefit from an expenditure of public funds must be the citizens or constituents of the jurisdiction making the expenditure. The benefit to the unit’s citizens or constituents is a far more important concern than the location of the activity.

Courts have upheld expenditures of public funds on activities or projects located outside the jurisdiction of a unit so long as the primary benefit was for the unit’s citizens or constituents. In Martin County v. Wachovia Bank & Trust Co., the state supreme court held that Martin County did not violate the public purpose clause by paying the majority of the costs of building a bridge between it and Bertie County, even though most of the structure was located in Bertie County. In so holding, the court focused on the benefit of the bridge project to Martin County citizens. Furthermore, it is okay if the benefit extends beyond a unit’s citizens or constituents.

As long as the local benefit accompanies the broader benefit, the activity may serve a public purpose. In Briggs v. City of Raleigh, the supreme court rejected a challenge to a legislative grant of authority to the municipality to issue general obligation bonds, upon voter approval, to provide $75,000 of funding to the state fair. The state fair was located just outside the city limits. Nonetheless, it was a public purpose for the municipality to support the state fair to retain it within its vicinity. Although the fair promoted the general welfare of the citizens of the state and not just the citizens of Raleigh, its location provided a unique benefit to them. Note that in both these cases the local units had statutory authority to make the extraterritorial expenditures. As discussed below, statutory authority is necessary to satisfy the public purpose clause.

Private Benefit Ancillary to Public Benefit

There is another element to the benefit inquiry. An expenditure of public funds must “primarily benefit the public and not a private party.” That does not mean, however, that private individuals or entities cannot gain from a government undertaking.

In fact, private individuals and entities benefit from most, if not all, government activities. When fire personnel suppress a fire and save a residential structure, it benefits the owners/occupants of that structure. When a municipality runs recreational summer camps, it benefits the participants in those camps. When a county builds a new school building, it benefits the students who are educated there. When a water and sewer authority expands its water line to a new subdivision, it benefits the property owners/occupants in that area. Given this reality, it is not surprising that the state supreme court has held that the “fact that a private individual benefits from a particular [government] transaction is insufficient to make out a claim under [the public purpose clause].” The court has further opined, “[i]t is not necessary, in order that a use may be regarded as public, that it should be for the use and benefit of every citizen in the community. It may be for the inhabitants of a restricted locality, but the use and benefit must be in common, and not for particular persons, interests, or estates.”

The public purpose clause requires that the general benefit from the government expenditure outweigh private, individual gain. In other words, “the ultimate net gain or advantage must be the public’s as contradistinguished from that of an individual or private entity.” If an expenditure “will promote the welfare of a state or a local government and its citizens, it is for a public purpose.” In Bridges v. Charlotte, the supreme court held that it was a public purpose for Charlotte to contribute to a retirement system for its public employees. Obviously, the individual employees were direct beneficiaries of the contributions. The court, however, based its holding on the fact that the employees were serving a public purpose by working for the government entity. The retirement payments were merely an incentive to attract and retain employees.

Courts often resort to balancing public and private benefits, invalidating an expenditure only if the private benefit is found to be predominant. Unfortunately, as several courts have noted, “[o]ften public and private interests are so co-mingled that it is difficult to determine which predominates.”

This issue comes up most often in the context of expenditures for community and economic-development programs, with the outcome of the analysis largely depending on how the benefits are characterized. In Mitchell v. North Carolina Industrial Development Financing Authority, for example, the supreme court determined it was not a public purpose to use state funds to acquire sites and construct and equip facilities for private industrial development. Significantly, the court considered the “benefits” to simply constitute a windfall available to only a few private companies at the expense of other companies and of the public generally. It thus found that the expenditure of public funds for this purpose did not serve a public purpose. Contrast that with the court’s later decision in Maready v. City of Winston-Salem, upholding a lower court ruling that economic-development incentive grants to private businesses did not violate the public purpose clause. In this case, the court took a much broader view of these “benefits,” stating that the ultimate goal of providing such incentives to one or more private entities was to improve the community at large—through, among other things, increased tax revenues and job opportunities. The Maready court held that a public purpose exists if the “public advantages are not indirect, remote, or incidental; rather they are directly aimed at furthering the general economic welfare of the people of the communities affected.” The case appears to reflect the court’s recognition of the “trend toward broadening the scope of what constitutes a valid public purpose that permits the expenditure of public revenues” in modern society. Of course, there is a great deal of subjectivity in this analysis, which is why the courts appear to be fairly deferential to the legislature’s determination that a particular activity benefits the public.

That does not mean there are no limits to what constitutes a public purpose. As Tyler Mulligan discusses in Chapter 15, “Financing and Public-Private Partnerships for Community Economic Development,” it probably is a mistake to assume that all economic-development incentive agreements will pass constitutional muster. Several state court of appeals opinions appear to interpret the Maready holding somewhat narrowly. This is still an evolving area of the law, and local units should proceed cautiously.

Does a local government entity have to document the benefit to its citizens before undertaking a particular activity? For most activities the answer is “no.” For some expenditures, however, the authorizing legislation requires a unit’s governing board to make specific findings as to the need or potential benefit of the undertaking. And in limited circumstances, a board must first consider citizen input or receive citizen approval before proceeding.

The courts also generally have not required a unit to engage in a formal benefit analysis (beyond what is required by the enabling statute). There are a few exceptions. As noted by Tyler Mulligan in the above-referenced chapter, the court seems to require that a unit make findings and abide by procedural formalities, some of which are not statutorily mandated, before it engages in certain economic-development activities. These are aimed at ensuring the necessity of the economic-development incentive, providing for sufficient public input, and confirming adequate public benefit from the expenditure.

The supreme court also has held that before purchasing or constructing an off-street parking facility, a local government must adopt a resolution finding that local conditions of traffic, congestion, and the like necessitate the facility. Furthermore, a public hearing must be held before the resolution is adopted. (In recent years, off-street parking has become a common municipal undertaking. It is not clear that a court would continue to impose these special procedural requirements.)

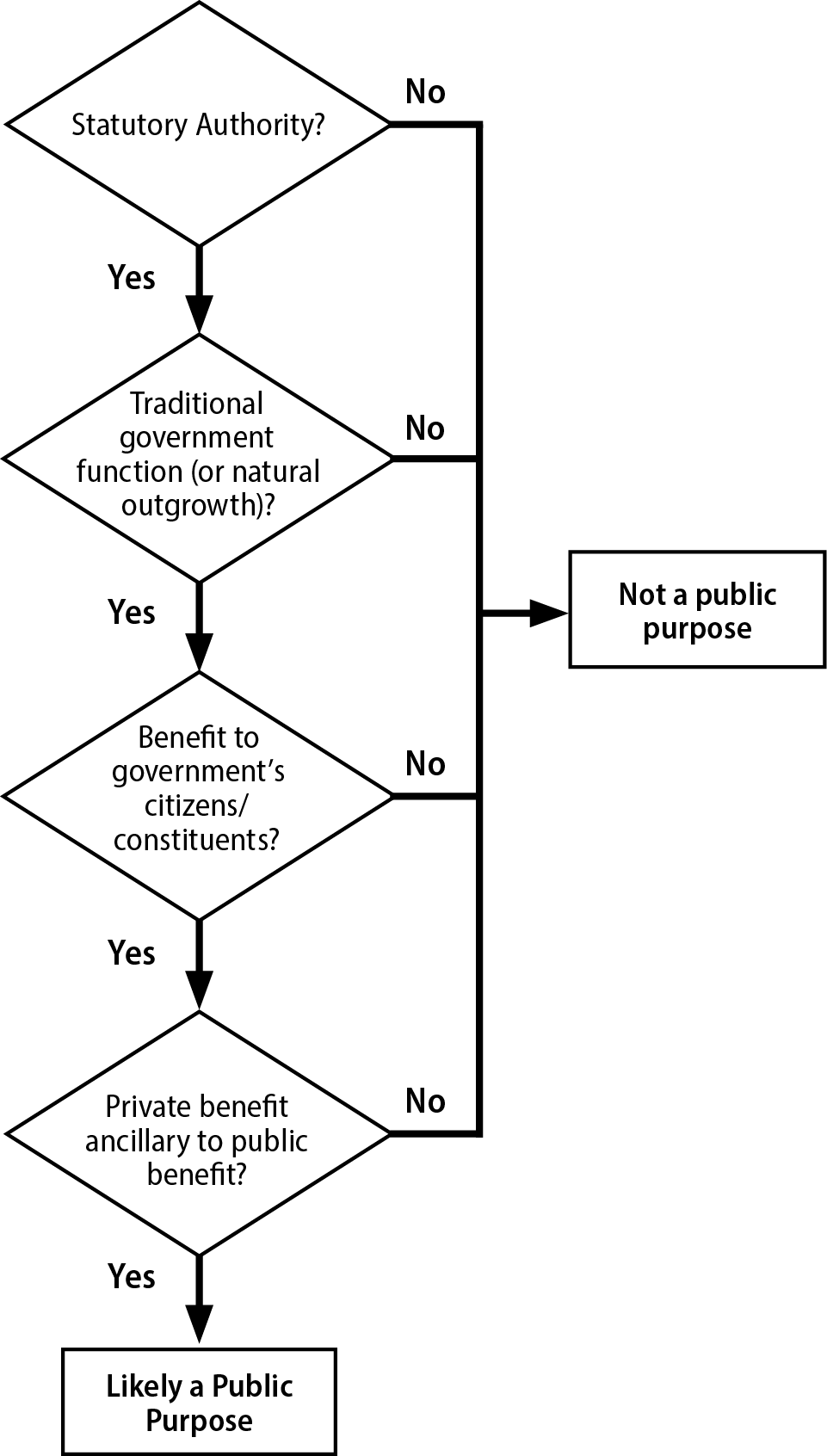

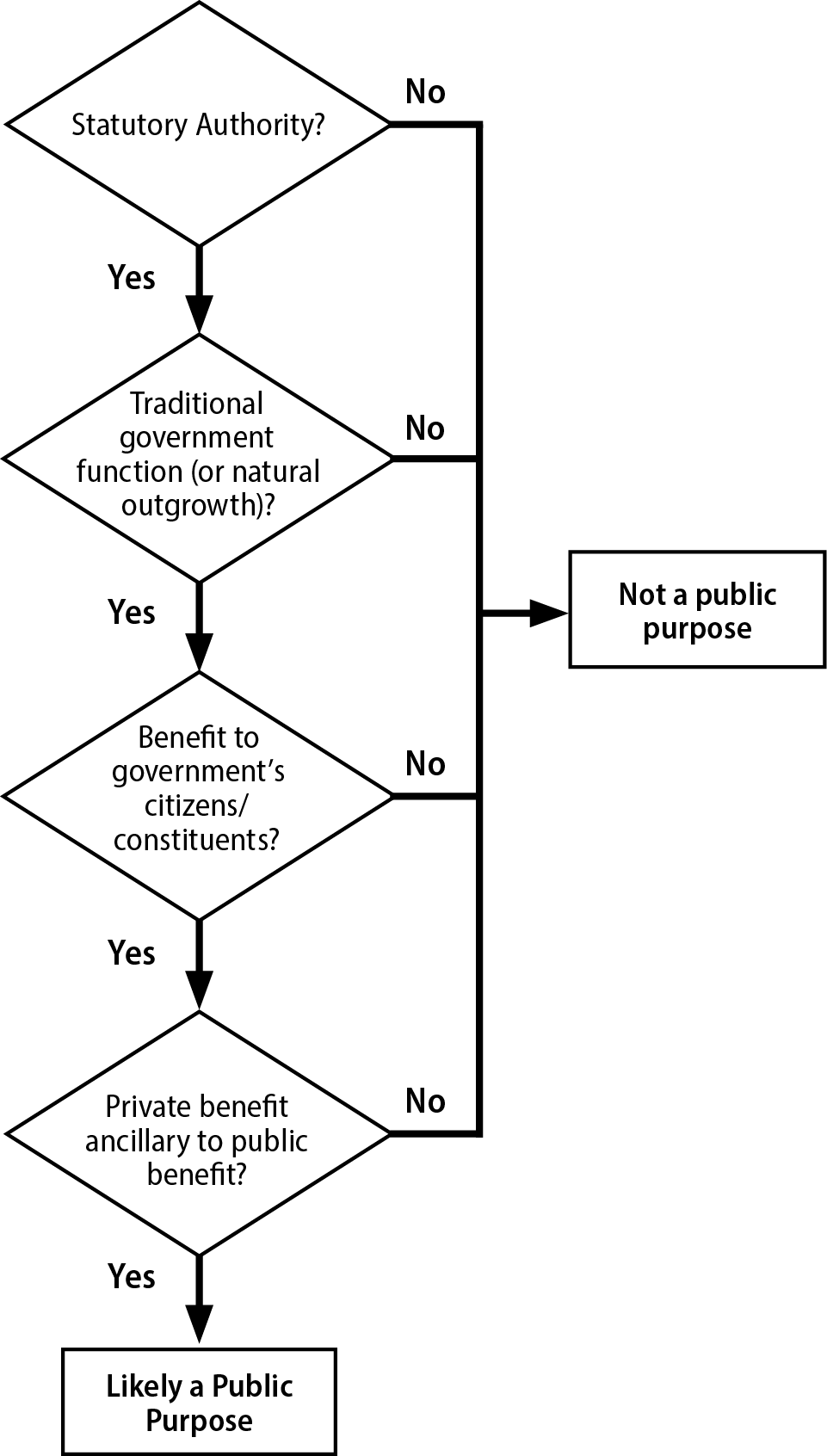

Applying Framework to Proposed Government Activity

There is substantial case law related to the public purpose clause. The cases cited above, however, are representative of the current framework North Carolina courts use to analyze this issue. Local officials may adapt this framework to provide prospective guidance about whether a proposed activity serves a public purpose. A unit must first determine if there is statutory authority for the undertaking. Statutory authority is necessary but not always sufficient. A local government should also ensure that both the means used and the ends sought constitute a traditional government activity or a natural extension or outgrowth of a traditional government activity. Furthermore, the activity must benefit the citizens of the unit making the expenditure generally. That does not mean it has to benefit all citizens equally. It also does not mean that the proposed expenditure of public funds cannot significantly and directly benefit specific individuals or entities. But the overall purpose of the activity must be to benefit the unit and its citizens, and, ultimately, this broader public benefit should predominate over the benefit to any single individual or entity. Figure 1.1 provides a flowchart process for local government officials to use when analyzing whether or not a proposed expenditure serves a public purpose.

Funding Nonprofits and Other Private Entities

How does this framework apply to funding requests from nonprofits and other private entities? Such requests are common and can range from a simple contribution to a community festival to subsidizing the capital and/or operating budget of the private entity. As stated above, both counties and municipalities have constitutional and statutory authority to contract with private entities. There is an important limitation on this authority, though. The appropriations ultimately must be used to “carry out any public purpose that the [local governments are] authorized by law to engage in.”

Thus, the statutory authorization incorporates the constitutional public purpose requirement. It also places a further limitation on the appropriation of public funds to private entities—the private entity that receives the public funds is limited to expending those funds only on projects, services, or activities that the local government could have supported directly. In other words, if a municipality or county has statutory authority to finance a particular program, service, or activity, then it may give public moneys to a private entity to fund that program, service, or activity. But a municipality or county may not grant public moneys to any private entity, including nonprofit agencies or other community or civic organizations, if the moneys ultimately will be spent on a program, service, or activity that the government could not fund directly. This authority allows local governments to contract with private entities to operate government programs or provide government services. It also allows local governments to support private entities, at least to the extent that those private entities seek to provide programs, services, or activities that a local unit is authorized to provide directly.

For example, a local unit may appropriate funds to a community group, nonprofit, or even a religious organization to fund a community festival that is open to all citizens of the unit because the local unit has statutory authority to undertake the activity itself. However, with few exceptions, a local unit may not appropriate funds to that same organization to finance capital projects or to fund the organization’s general operating expenses, because the unit does not have authority to spend moneys directly on this type of project. Perhaps a more common example arises when a local unit is asked to become a dues-paying member of a civic or community organization, such as a chamber of commerce or rotary club. The local government must be very careful to ensure that its dues are expended only for purposes that the government could have funded directly. The local government should ask the organization to make a request for funds for a specific project, service, or activity and then execute a contract with the organization for this purpose.

When a local government contracts with a private entity, it must ensure that public funds are expended for the statutorily authorized purpose. At a minimum, a local government must require a recipient organization to provide some sort of performance accounting. The North Carolina Supreme Court has provided some guidance to local governments on this issue, sanctioning a particular oversight method in Dennis v. Raleigh. That case involved a challenge to an appropriation of funds by the City of Raleigh to a local chamber of commerce to be spent on advertising the city. The chamber of commerce engaged in a variety of activities, some of which were unlikely to be considered public purposes. Thus, the city sought to ensure that the public funds it appropriated to the chamber of commerce were spent appropriately. The city put in place three separate “controls.” First, the appropriation to the chamber of commerce was specific—it stated that the moneys were to be used “exclusively for . . . advertising the advantages of the City of Raleigh in an effort to secure the location of new industry.” Second, the city council reserved the right to approve each specific piece of advertising. Third, the chamber of commerce had to account for the funds at the end of the fiscal year. On the basis of the control exercised by the city over the expenditure of the public funds, the court upheld the appropriation.

The first and third “controls” placed on the chamber of commerce by the City of Raleigh in Dennis likely are particularly instructive. These controls parallel the appropriation and annual audit requirements placed by the Local Government Budget and Fiscal Control Act (LGBFCA) on moneys spent directly by a municipality or county. At a minimum, a local government should provide clear guidelines and directives to a private entity as to how and for what purposes public moneys may be spent, and the unit should require some sort of accounting from the private entity that it fully performed its contract obligations. Additionally, a local unit may require a private entity to provide a financial accounting. The accounting does not have to rise to the level of an official audit, though G.S. 159-40 authorizes local governments to require any nonprofit agency receiving $1,000 or more in any fiscal year (with certain exceptions) to have an audit performed for the fiscal year in which the funds are received and to file a copy of that report with the local government. And state law requires any nonprofit corporation that receives more than $5,000 of public funds within a fiscal year, in the form of grants, loans, or in-kind contributions, to provide certain financial information upon written request from any member of the public.