Chapter 5

Property Tax Policy and Administration

by Christopher B. McLaughlin

Introduction

The goal of this chapter is to educate North Carolina local government officials about the basic structure and operation of our state’s property tax system. It should give local officials the information they need to know what local governments must do, what they may do, and, perhaps most importantly, what they cannot do with property taxes. For more details on the topics discussed below, please see Christopher B. McLaughlin, Fundamentals of Property Tax Collection Law in North Carolina (UNC School of Government, 2011).

Non-Legal Considerations

This chapter focuses mainly on the legal issues surrounding property taxes. But local governments also face a number of important non-legal decisions concerning property tax policy and practice.

The most basic of these decisions is whether the local government wishes to levy a property tax. Although property taxes are optional, all 100 counties and nearly all the state’s 500-plus municipalities levy this type of tax.

Taxpayers may wonder why local governments tax at all in light of the substantial federal and state taxes already affecting their incomes and activities. The simple answer to this question is that without property tax revenues, local governments would be forced to drastically cut services. Property taxes are the single largest source of unrestricted revenues for both counties and municipalities in North Carolina. Revenue from these taxes supports the wide variety of services provided by local governments.

The property tax is popular among local governments because it is one of the few sources of revenue under their complete control. Most other taxes are levied at rates set by state statutes or produce revenue that must be shared with the state or with other local governments. Not so for property tax rates and revenues, which are controlled entirely by local governments and subject only to a rather generous statutory maximum rate.

Property tax rates vary across the state from just a few pennies to more than $1 per $100 of property value. The legal parameters concerning the tax rate calculation are discussed in “The Property Tax Rate” section, below. But for the most part, the tax rate decision rests on a policy question beyond the scope of this book: What level of services should the local government provide and how should those services be funded?

Other non-legal decisions include how to organize the tax office, whether a municipality should collect its own taxes or contract with the county for such services, what types of enforced collection actions the collector will be authorized to pursue, and when countywide reappraisals of real property should occur. This chapter discusses the relevant statutory constraints and identifies best practices, but it does not attempt to suggest the correct answers to these questions. As with most issues involving local government, there is no one-size-fits-all approach to property taxes.

The Big Picture

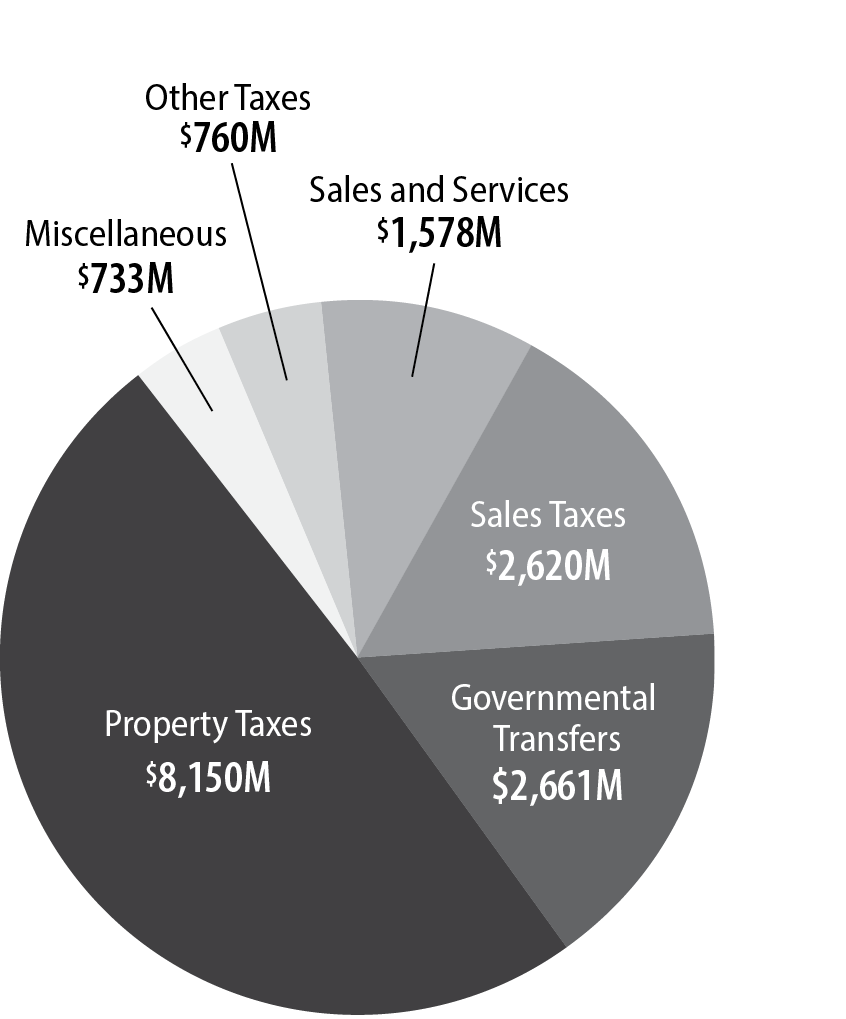

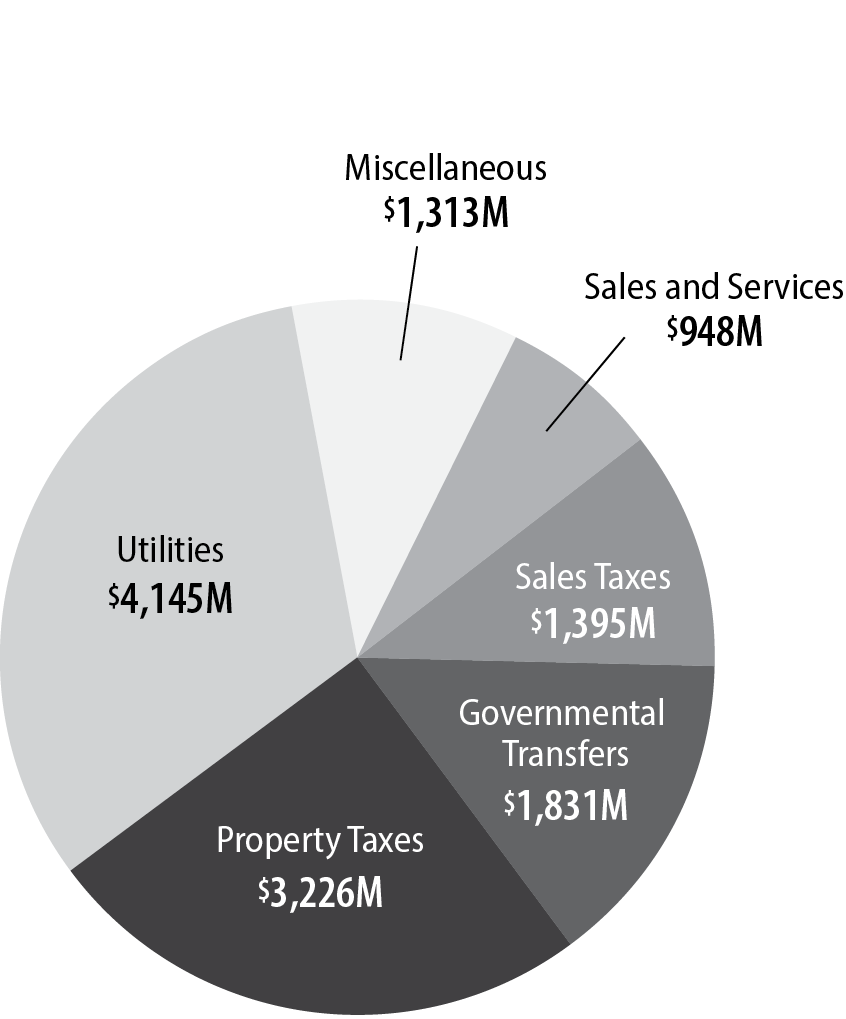

As noted above, property taxes represent the single largest source of unrestricted revenue for both counties and municipalities. For fiscal year 2020–2021, property taxes represented 49 percent of county revenues and 25 percent of municipal revenues. Figures 5.1 and 5.2 illustrate the relative importance of property taxes as compared to other revenue sources. Note that both figures exclude debt proceeds, which must be paid back in the future using other revenue sources and therefore are not truly revenue sources.

Although utility fees represent a larger percentage of municipal revenues than do property taxes, those funds are not unrestricted revenues because generally they must be used to cover the cost of providing those utilities. Were utility fees and charges excluded from the calculation, property taxes would represent more than 36 percent of municipal revenues.

The Governing Law and the Cast of Characters

Article V (finance), Section 2 (state and local taxation) of the North Carolina Constitution sets the basic ground rules for property taxes. Chapter 105, Subchapter II of the North Carolina General Statutes (hereinafter G.S.), commonly known as the Machinery Act, provides the details.

Actors at both the state and local levels play major roles in the property tax process. Table 5.1 identifies the principal characters at both levels of government.

State Level

|

Local Level

|

- General Assembly

- Department of Revenue, Local Government Division

- Property Tax Commission

- Court of Appeals

- Supreme Court

|

- Governing Board

- Assessor (County)

- Tax Collector

- Board of Equalization and Review (County)

|

As mentioned above, the property tax process is governed by statutes enacted by the General Assembly as part of the Machinery Act. The state Local Government Division of the N.C. Department of Revenue (NCDOR) is charged with ensuring that local governments adhere to the Machinery Act’s requirements. This division also provides education, training, and guidance to local government tax officials and assesses and allocates public-service-company property to the counties so that it can be subject to local property taxes.

Note that NCDOR’s Local Government Division is distinct from the Local Government Commission (LGC), which operates out of the N.C. Department of the State Treasurer. The LGC monitors the fiscal and accounting practices of the state’s local governments but does not play a direct role in property tax administration.

County boards of equalization and review, the state Property Tax Commission, the state court of appeals, and the state supreme court are all involved with the resolution of appeals concerning property tax values and property tax exemptions and exclusions.

An assessor is responsible for listing and assessing all taxable property in a county for property taxes. In other words, he or she must determine the what, the where, the who, and the how much for all property that will be taxed for the coming fiscal year. A tax collector must collect the taxes levied on that property, if necessary by use of the enforced collection remedies available under the Machinery Act and other statutes. In many counties, the county commissioners have chosen to appoint a single individual as both assessor and tax collector under the title of “tax administrator.”

The role of the local government governing board in the property tax process is summarized in Table 5.2. Table 5.3 lists the important dates in the property tax calendar. More details on all these issues are provided in subsequent sections of this chapter.

Board of County Commissioners

|

Town/City Council

|

- Adopts property tax rate annually

- Appoints assessor and tax collector

- Reviews performance of assessor and tax collector

- Accepts settlement of prior year’s taxes from tax collector and charges tax collector with responsibility for current year’s taxes

- Decides when to conduct countywide reappraisals of real property (at least every eight years)

- Appoints Board of Equalization and Review (the county commissioners may serve as this board)

- Rules on taxpayer requests for refunds and releases

|

- Adopts property tax rate annually

- Appoints tax collector or contracts with county for tax collection

- Reviews performance of tax collector

- Accepts settlement of prior year’s taxes from tax collector and charges tax collector with responsibility for current year’s taxes

- Rules on taxpayer requests for refunds and releases

|

|

January 1

|

- Listing date (ownership, situs, value, and taxability determined)

- Tax liens attach to real property

|

|

July 1

|

- Fiscal year begins

- Deadline for adoption of new budget and tax rate

|

|

September 1

|

- Discounts end (if offered)

- Taxes due

|

|

January 6 (following year)

|

- Taxes become delinquent, interest accrues, and enforced collections may begin

|

|

June 30 (following year)

|

- Fiscal year ends, annual collection rate is determined

|

Real Property versus Personal Property

Collection remedies under the Machinery Act differ depending on whether the property being taxed is real or personal. Real property is essentially land, buildings, and things that are permanently affixed to those buildings—think of light fixtures or kitchen cabinets. Personal property is everything else: vehicles, boats, planes, business equipment, and so forth. With very few exceptions, personal property is taxable only if it is tangible. Intangible personal property—such as cash, stocks, bank deposits, patents, and franchise rights—is not taxable.

Why Cars Are Different

Cars, trucks, vans, motorcycles, and trailers with valid registrations and license plates are called “registered motor vehicles” (RMVs) by the Machinery Act. Although they are considered personal property under the Machinery Act, RMVs are subject to very different tax rules than those applied to other types of personal property.

In a nutshell, the taxation of RMVs is tied to the registration and renewal process. Registration of most motor vehicles is staggered throughout the year so that different due dates and delinquency dates apply for different RMV taxpayers. Under the “Tag & Tax Together” program which debuted in 2013, owners pay property taxes on their vehicles at the time they obtain their initial registrations or renew their registrations for those vehicles with the N.C. Division of Motor Vehicles (DMV). If the owner refuses to pay the taxes, the DMV will refuse to register the motor vehicle. Under this new system, local governments no longer have any collection authority or responsibility for the property taxes they levy on registered motor vehicles. See the section titled “Registered Motor Vehicles,” below, for more details on RMV taxes.

The Property Tax Rate

Although local governments are not required to levy property taxes, nearly all do. The rates at which they levy those taxes vary greatly, as Table 5.4A indicates. Traditionally, the lowest rates were found in counties located along the coast and in the mountains in counties with lots of expensive vacation homes.

|

|

Lowest Rate

|

Highest Rate

|

Median Rate

|

|

Counties

|

.320 (Watauga)

|

.990 (Scotland)

|

.66

|

|

Municipalities

|

.013 (Wesley Chapel)

|

.920 (Enfield)

|

.47

|

North Carolina Department of Revenue.

Property tax rates for a particular local government are generally capped at $1.50, but that cap is subject to many exceptions. For example, there is no statutory limit on the rate for property taxes used to fund schools or jails. And for uses that are subject to the statutory cap, a local government may obtain voter approval to exceed the $1.50 maximum tax rate.

The $1.50 cap applies to individual taxing jurisdictions, not to individual taxpayers. A taxpayer who lives in a municipality could very well wind up paying a total property tax rate greater than $1.50 because that taxpayer’s property is subject to both county and municipal taxes. As a result, a municipality need not worry about the county’s property tax when setting its own rate, or vice versa.

The amount of revenue that each county can generate from its property tax depends on that county’s tax base, of course. As Table 5.4B demonstrates, county tax bases vary widely. A 1¢ increase in Tyrrell County’s property tax would produce an additional $43,300 in tax revenue. In Mecklenburg County, that same 1¢ property tax rate increase would generate $19,000,000.

|

Smallest

|

$433 Million

|

Tyrrell County (population 3,254)

|

|

Largest

|

$190 Billion

|

Mecklenburg County (population 1,122,000)

|

|

Median

|

$16 Billion

|

|

|

Average

|

$13 Billion

|

|

North Carolina Department of State Treasurer.

Article V, Section 2(2) of the North Carolina Constitution requires that all property within a specific taxing jurisdiction must be subject to the same tax rate. This uniformity requirement prohibits local governments from adopting different tax rates for different property or for different areas of that jurisdiction. For example, a county could not adopt one tax rate for real property and a different tax rate for motor vehicles. Nor could a county choose to adopt one tax rate for its incorporated areas and a different tax rate for its unincorporated areas.

The only exception to the uniformity requirement is the constitutional provision that permits special tax districts. Often called service districts, these tax districts are authorized by Article V, Section 2(4) of the North Carolina Constitution to fund additional services in their geographic areas. Multiple tax districts are permitted in the same local government, so long as each tax district is created for a permissible purpose. The uniformity requirement applies to these special districts in that the additional tax rate levied in a particular district must be uniformly applied to all property sited in that district.

Counties most often use special tax districts to fund fire protection in unincorporated areas, but they can also use them to fund such services as trash collection, sewer and water systems, and beach erosion control. Municipalities can use special tax districts to fund many of those same services, but they more often create districts for downtown revitalization projects. This category is broadly defined to cover a variety of expenditures, including new parking facilities, improved lighting, additional police protection, and tourism promotion within the downtown core.

Another type of special tax district is a special supplemental school district. The supplemental school district tax must be approved by voters before it can be levied and must be used only to fund the public schools in that district. Once adopted, a supplemental school tax applies to all property within that particular school district.

The taxes levied in a special tax district count toward the $1.50 cap on general property tax rates. This means that the total of regular property taxes and special district taxes levied by a local government on a particular piece of property cannot exceed $1.50 for certain uses unless the local government obtains voter approval to exceed that cap.

Use-Specific Taxes

A local government may adopt a single property tax rate to satisfy all its budgetary needs, or it may adopt multiple tax rates with the revenue from each earmarked for a specific use. For example, instead of funding police and fire protection services out of its general property tax revenue, a municipality could choose to adopt two property tax rates: one for general fund revenue and one to fund police and fire services.

There is no limit on the number of different use-specific property tax rates that may be adopted by a local government, so long as each such tax applies uniformly to all taxable property within the jurisdiction. Use-specific taxes may be adopted as part of a local government’s annual budget and do not require voter approval.

A key difference between use-specific property taxes and special tax district taxes is that use-specific taxes must apply to the entire jurisdiction. Special tax district taxes may be levied on portions of a jurisdiction to fund specific services in that district.

The North Carolina Supreme Court has ruled that spending decisions by local governments are not bound by use-specific property taxes. A local government may change its spending for a particular use regardless of what it promised to spend on that use in its budget through a use-specific tax rate.

For example, assume that a county adopts a $.50 general tax rate, a $.12 tax rate for law enforcement, and a $.02 tax rate for libraries. Based on its budgeted tax base, the $.12 tax would raise $1,200,000 for county law enforcement and the $.02 tax would raise $200,000 for county libraries. Despite the adoption of these use-specific taxes, the county could choose to spend more or less than these amounts on law enforcement and libraries in the coming fiscal year. Voters may not take kindly to such variations from the budget, but they are legal.

Setting the Tax Rate

Property taxes are levied on a fiscal year basis despite the fact that many of the important dates on the property tax schedule seem to be configured around the calendar year. A local government that levies property taxes must set its property tax rate(s) in its annual budget, which should be adopted by July 1, the beginning of the fiscal year.

Until a budget is adopted, there can be no property tax levy. Although interim budgets are permitted, they authorize only continued spending by local governments and not the levy of taxes. A delay in the adoption of the budget can delay property tax collections and do serious harm to a local government’s revenues.

The property tax rate should be based on the amount of revenue the local government needs to balance its budget after all other revenue sources are accounted for, given the expected tax base for the coming year. Obviously, this amount will be driven by important decisions regarding what services the local government can and should provide.

When balancing the budget with property taxes, a local government must be realistic about how much of its tax levy it will actually collect. While property tax collection percentages are generally very good—99 percent on average—no local government collects every penny of its property taxes. For budget purposes, state law prohibits local governments from assuming a higher collection rate for the coming year than it experienced in the current year.

Changing the Tax Rate

Once the total tax rate is set in the budget, the governing board is generally prohibited from changing it. Absent an order from a judge or from the Local Government Commission, the only justification for adjusting a tax rate after adoption of the budget is when the local government receives revenues that are substantially different from what was expected. And even then, the change must occur before January 1 following the start of the fiscal year. For example, if a governing board wished to change its 2023–2024 tax rate due to a substantial change in revenues, it would need to act before January 1, 2024.

What type of events could justify a change in the total tax rate under this standard? The relevant statutes do not provide additional details, but presumably changes could occur after a misfortune such as a bankruptcy filing by a large industrial taxpayer that would prevent collection of a substantial portion of the local government’s property tax levy or the elimination of an important revenue source due to new legislation enacted by the General Assembly. Good news—such as the creation of a major new revenue source for the local government—could also justify a mid-year change in the tax rate, but such occurrences are rare.

As mentioned above, local governments may adopt multiple tax rates for different uses. These use-specific rates may be changed during a fiscal year without regard for statutory restrictions so long as the total tax rate levied by the local government does not change.

Consider again the example in which a county adopts a general tax rate of $.50, a law enforcement tax of $.12, and a library tax of $.02, for a total combined rate of $.64. The county would be free to alter any or all of its three different tax rates so long as the total combined rate still equaled $.64.

The Revenue-Neutral Tax Rate

To help taxpayers compare tax rates before and after countywide reappraisals of real property, local governments are required to calculate and publish revenue-neutral tax rates (RNTRs) following their reappraisals.

The RNTR would produce the same amount of revenue using the new tax base as was produced in the present year from the existing tax rate and tax base. In other words, if a new tax rate adopted by a governing board is higher than the RNTR, then the local government has increased its total property tax levy, and if the new rate is lower than the RNTR, the local government has decreased its total property tax levy.

In normal economic times, tax bases increase after reappraisals. When the tax base increases, the tax rate can be lowered without decreasing tax revenue. Therefore, the RNTR is normally lower than the existing tax rate. However, when market prices drop, as they have done of late in many areas of the state, a local government’s tax base can decrease after a reappraisal. In these circumstances, the government board that wishes to keep revenues constant must raise the tax rate. As a result, the RNTR will be higher than the existing tax rate.

Local governments are not required to adopt the RNTR, but they must publish it as part of their annual budget process. Even if the RNTR is adopted, individual taxpayers may see their tax bills increase or decrease because their individual property appreciated or depreciated more than did the tax base in the aggregate. Much confusion surrounds the RNTR, in large part because, despite its name, it does not guarantee that taxpayers’ bills will remain constant.

For example, assume that Carolina County’s tax base increased by 10 percent following its 2023 reappraisal. The RNTR is calculated to be $.50 per $100 of value, a bit lower than the county’s 2022–2023 tax rate of $.55 per $100 of value. The county commissioners decide to adopt the RNTR as the tax rate for 2023–2024 and proudly announce that they have avoided a tax increase. However, when the 2023 tax bills are mailed in August, Tommy TarHeel is furious because his new tax bill is higher than last year’s tax bill.

How can this be? The likely answer is that Tommy’s real property appreciated more than 10 percent, which was the average increase in value for all real property in the county. Assume that Tommy’s real property tax appraisal increased from $100,000 to $150,000 as a result of the 2023 reappraisal. For 2022–2023, Tommy’s tax bill was $550 ($100,000/100 × $.55). For 2023–2024, his tax bill is $750 ($150,000/100 x $.50). The drop in the tax rate was not enough to offset the increase in Tommy’s tax appraisal, meaning that Tommy’s tax bill increased by $200 despite the county’s adoption of the RNTR.

By adopting the RNTR, a local government may keep its aggregate property tax revenue constant. But individual taxpayers’ bills are not guaranteed to remain constant because individual properties are likely to have appreciated or depreciated differently from the countywide tax base.

Listing and Assessing

The process of determining what taxable property exists in a jurisdiction, who owns it, and how much it is worth is known as listing and assessing property for taxation. The county assessor oversees this process, which is closely regulated by the Machinery Act and is intended to be (mostly) uniform from county to county. The only property over which the assessor does not have listing and assessing authority is public-service-company property, described in more detail below.

As a general rule, local government governing boards do not get involved with assigning tax values to individual properties. That process is accomplished by the assessor and his or her staff, ideally free from political pressures.

However, local government governing boards—especially boards of county commissioners—do retain some discretion as to how and when the process unfolds. These discretionary duties include

-

appointing the assessor and setting his/her term of office,

-

approving the budget for the assessor’s office,

-

deciding when to hold countywide reappraisals of real property,

-

ruling on taxpayer appeals of tax values and tax exemptions while sitting as the board of equalization and review (or appointing a separate board of equalization and review), and

-

waiving or refusing to waive discovery bills.

One property tax issue over which local governments have no authority is the creation of property tax exemptions. The North Carolina Constitution grants this authority exclusively to the General Assembly. As a result, property tax exemptions are products of state statutes, not local ordinances. Counties and municipalities may not create their own exemptions from property taxes. Nor may they decide to ignore exemptions mandated by the Machinery Act.

This section briefly describes the listing and assessing process and the appropriate role for governing boards in that process. Readers who seek more details should take a look at A Guide to the Listing, Assessment, and Taxation of Property in North Carolina, a comprehensive guide to the process written by my School of Government colleague Shea Riggsbee Denning.

Appointing the Assessor

The assessor, appointed by the board of county commissioners, is responsible for listing and assessing all taxable property in the county. This process includes determining the situs—a fancy word for taxable location—of that property, determining who owns that property, deciding whether that property and its owner are eligible for an exemption or exclusion from tax, and, perhaps most controversially, assigning a value for tax purposes to that property.

The Machinery Act creates some minimum qualifications for assessors, but for the most part the board of county commissioners retains great discretion as to who should serve in this role. Candidates must be at least twenty-one years of age, must hold a high school diploma or equivalent, and must be certified by the N.C. Department of Revenue within two years of taking office. Certification involves passing four assessment courses and a comprehensive exam. The assessor must be appointed for a fixed term set by the county commissioners that can vary from two to four years. Once the assessor’s term length is set by the commissioners, it cannot be changed until after the term ends or after the assessor is removed from office.

Unlike most employees in most counties, assessors are not at-will employees and cannot be removed from office at the discretion of the commissioners. An assessor may be removed from office before his or her term ends only for “good cause,” a term not defined by the Machinery Act. However, similar good cause provisions covering appointed officials elsewhere in the General Statutes suggest that adequate grounds for removal include inefficiency, misconduct in office, and commission of a felony or other crime involving moral turpitude. In other words, the conduct that justifies the removal must either be directly tied to the assessor’s job performance or be so serious as to call into question the assessor’s fitness for office. For example, the failure to pay property taxes in a timely fashion likely would justify the firing of an assessor, but a conviction for driving under the influence might not.

If the county commissioners wish to remove the assessor from office, they must first provide the assessor with written notice of that intent and the opportunity to be heard at a public session of the board. For obvious reasons, the county attorney should be intimately involved with this process.

The Machinery Act does not create term limits for assessors. A board can repeatedly reappoint a particular assessor for as long as it wishes.

What, Where, Who, and How Much?

The what, where, who, and how much decisions concerning property taxes on personal property are made as of the annual listing day, which is the January 1 before the fiscal year begins. For taxes on real property, the how much decisions (appraisals) are made as of January 1 of the reappraisal year, but ownership and taxability decisions are made as of January 1 each year, just as they are for personal property. In other words, a snapshot is taken every January 1, and the results of that snapshot control property taxes for the coming fiscal year.

For example, if Tom Taxpayer buys a new boat on February 1, 2023, he will not be required to list that boat for 2023–2024 property taxes because he did not own the boat on January 1. If Tina Taxpayer owns a house in Carolina County on January 1, 2023, that house is taxable by the county for the 2023–2024 fiscal year even if it burns to the ground the very next day. If Tim Taxpayer owns a vacant lot in Carolina County on January 1, 2023, and breaks ground on a new house on that lot on January 2, the new house will not be taxable by the county for 2023–2024 because it did not exist on January 1, the listing day. The house first will be listed and taxed as of January 1, 2024, meaning it first will be taxed by the county in the 2024–2025 fiscal year. Construction that is partially complete as of January 1 should be assessed a percentage of its estimated value once complete.

Situs

The situs (taxable location) of real property should be easily determined and immutable except when municipalities change their boundaries through annexation or de-annexation or, less often, when two counties adjust their borders. But the situs of personal property—cars, boats, and planes especially—can present a major challenge. That movable property is not in a jurisdiction on January 1 does not necessarily mean that the jurisdiction cannot tax that property for the coming year.

With respect to personal property, situs means property that is more or less permanently located in a jurisdiction. For example, if a private jet is flown all over the country throughout the year but always returns to a hangar in Carolina County, Carolina County should be able to tax that plane even if it is not in the county on January 1.

Appraisal of Personal Property

The Machinery Act requires that all property be assessed for tax purposes at its “true value,” defined to be the property’s market value were it sold in an arms-length transaction between two willing, able, and informed parties under no compulsion to buy or sell the property.

As mentioned above, all taxable personal property—in other words, all taxable property that is not land or buildings—is appraised annually as of January 1. Generally tax appraisals for cars, boats, planes, factory equipment, and other personal property decrease from year to year because that property depreciates and loses value over time.

Appraisal of Real Property

The most time-consuming and controversial part of the property tax process is the countywide reappraisal of real property, during which all land and buildings are assigned new tax values. Just as is true for personal property, real property must be valued at its true market value that would be obtained in an arms-length transaction. Because foreclosure sales are involuntary sales, they are generally not considered when calculating appraisals.

Reappraisals—or “revals” as they commonly are called—must occur at least every eight years. Within this eight-year limitation, a county can choose whatever reappraisal cycle it prefers. A county is also free to change its reappraisal cycle in between reappraisals, so long as it stays within the eight-year limitation.

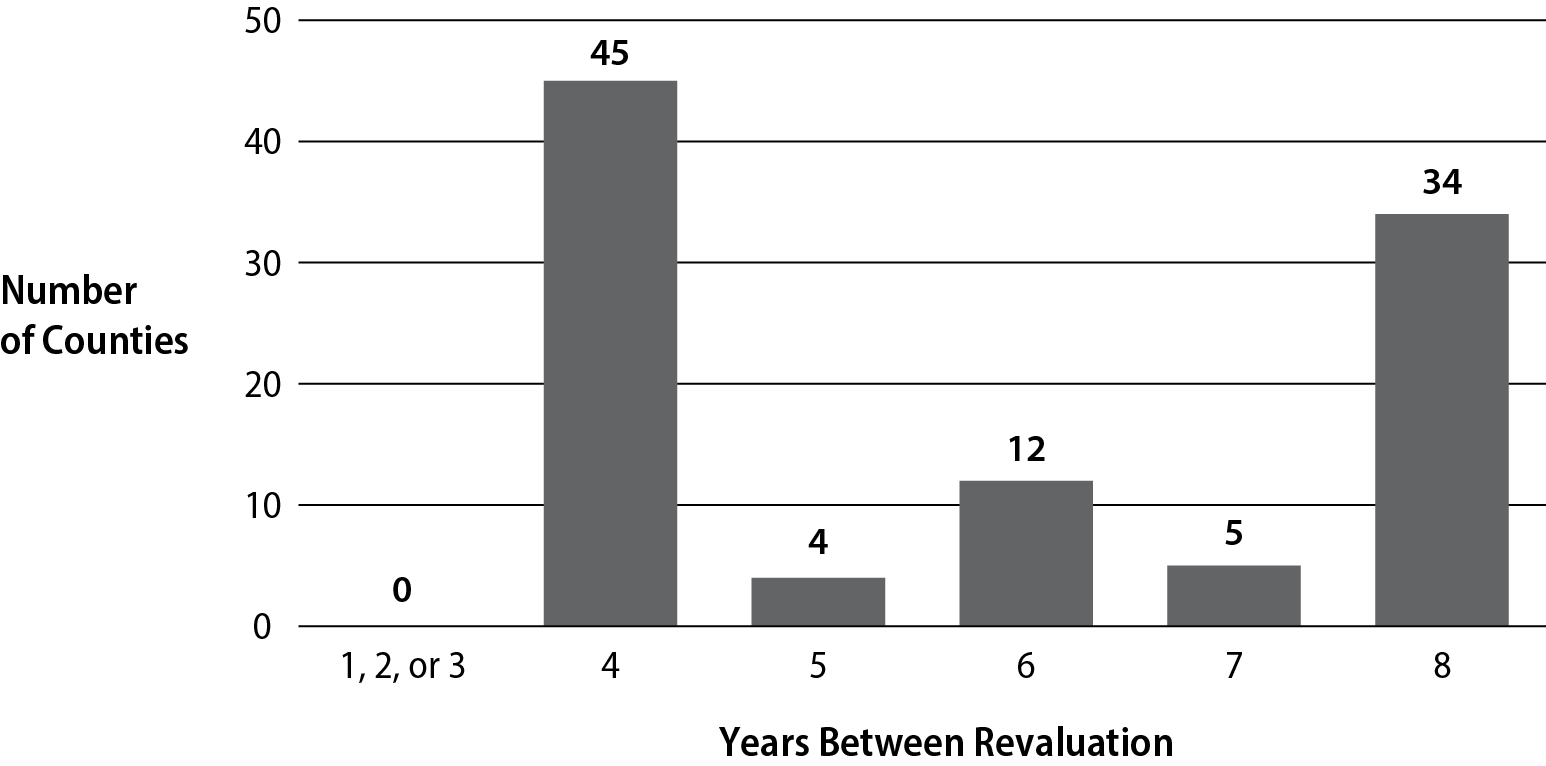

In an ideal world, every county would reappraise all of its real property every year so that its tax values would be pegged to true market value as closely as possible. But annual reappraisal of the many thousands of real estate parcels in each county is simply not practical from either an expense or a workload perspective. As Figure 5.3 demonstrates, just under half of the state’s 100 counties are on four-year cycles and about one-third of them are on eight-year cycles. This is a substantial change from a decade ago, when more than two-thirds of the state’s counties were on eight-year cycles.

North Carolina Department of Revenue, 2023.

Depending on the size of its assessor’s office, a county can either conduct a reappraisal using only in-house staff or hire external consultants to do some or all of the required appraisal work. The process involves what is known as a mass appraisal, meaning not every parcel of real property is inspected by appraisers. Usually a small representative sample of a county’s real property will be individually appraised. The rest of the county’s real property will be assigned tax values based on an analysis of market prices and physical characteristics at the neighborhood level.

Changes to Real Property Tax Values in Non-Reappraisal Years

In between reappraisals, real property tax values generally should change only due to physical or zoning changes to the property. Changes in general economic conditions or in the local real estate market should not be reflected in tax values until the next reappraisal.

For example, assume that Billy BlueDevil owns Parcel A that was appraised at $300,000 in Carolina County’s 2020 reappraisal. The county’s next reappraisal is not scheduled until 2024. Billy sells Parcel A to Tommy TarHeel in late 2022 for $400,000 in an arms-length, non-foreclosure transaction. Although the true market value of Parcel A may be $400,000 as of January 1, 2023, the tax value of Parcel A should not change until the next reappraisal in 2024. The tax value of Parcel A must remain its true market value as of January 1, 2020. The same would be true if Billy’s house sold in 2022 for less than its 2020 tax value.

Now assume that instead of selling Parcel A, Billy increases the size of his house on that lot by 2,000 square feet in 2022. This physical change to Parcel A should be reflected in the 2023 tax value of Parcel A. The tax value of Billy’s house would also need to be changed prior to the next reappraisal if it burned down or were rezoned to make it more or less valuable for future development or use.

Public-Service-Company Property

Only one type of property is assessed at the state level: real and personal property owned by electricity providers, gas companies, railroads, telephone service providers, and other public-service companies.

Each year these companies are required to list their taxable property with the N.C. Department of Revenue (NCDOR), which then assigns a tax value to that property and allocates that value to local governments for taxation. For real property, such as a power plant, the allocation is based on location. For movable personal property, such as buses and trains, the allocation is based on the miles driven in a jurisdiction, the miles of track in a jurisdiction, or a similar formula. If a local government’s sales assessment ratio falls below 90 percent in certain years, that local government can lose a percentage of its public-service-company property value. (See the next section for more on sales assessment ratios.)

Once public-service-company property value has been allocated to a local government, it may tax that property just as it taxes all other property in its jurisdiction. Unlike regular property tax appeals, appeals of public-service-company property tax values go directly to the state Property Tax Commission and are not handled at the county level.

Sales Assessment Ratios

Each year, NCDOR studies a sample of real estate sales from each county and compares the sales prices to the property tax appraisals of the sold properties. Foreclosures and other transactions that were not arms-length transactions are excluded from these studies. A ratio is created for each property by dividing the tax appraisal by the sales price. The median of all of the ratios is that county’s sales assessment ratio.

This ratio is a rough measure of how closely the county’s tax values reflect actual market values. Ideally the ratio would be 100 percent, meaning that, on average, tax appraisals are pegged right at market values. If the ratio is below 100 percent, then, on average, tax appraisals fall below market values. If the ratio is greater than 100 percent, then, on average, tax appraisals fall above market values.

In healthy economic times, sales assessment ratios decrease in the years following appraisals because tax values remain basically constant while market values slowly but steadily increase. When a county conducts its reappraisal, its sales assessment ratio will jump back up close to 100 percent. Only a handful of counties will have ratios over 100 percent, usually those few in which reappraisals have just been conducted and their tax values have been pegged slightly above the market. In weaker economic times, when real property prices are falling or are flat, more counties will have ratios under 100 percent.

The most recent sales assessment ratio from NCDOR reflects the strong real estate market experienced by most of the state in the past few years. Only three counties have sales assessment ratios above 100 percent, with the average ratio at 83.4 percent.

Why the Sales Assessment Ratio Matters

County leaders can use the sales assessment ratio to evaluate the effectiveness of their reappraisals. The ratio can also help predict how the county’s tax base will change in the next reappraisal: if a county’s sales assessment ratio is well above 100 percent, county leaders should be prepared for a drop in the tax base after the next reappraisal.

There are statutory reasons to pay attention to the sales assessment ratio as well. It is the basis for two Machinery Act provisions intended to promote more frequent appraisals of real property.

The first provision deals with public-service-company property. If a county’s sales assessment ratio falls below 90 percent in the fourth or seventh year after a reappraisal, then that county’s assessed value of public-service-company property will be reduced. The reduction will roughly equate to the actual sales assessment ratio: if the county’s ratio is 85 percent, the county will be allocated and will be able to tax only 85 percent of the full assessed value of the public-service-company property it would otherwise have been allocated.

The second provision involves mandatory reappraisals for counties with populations greater than 75,000. If such a county’s sales assessment ratio is below 85 percent or above 115 percent, then the county must conduct a reappraisal within three years. Thanks to the very strong real estate market across the state, in 2022, NCDOR reported that twenty-eight counties triggered mandatory reappraisals. That total is almost twice as many as had done so cumulatively in the previous fifteen years.

Property Tax Exemptions and Exclusions

Only the General Assembly has the authority to create exemptions from local property taxes. Local governments may not carve out their own exemptions, nor may they choose not to administer the exemptions created by the General Assembly. Although the Machinery Act uses two terms—exemption and exclusion—to describe statutes that partially or completely remove property from taxation, for the purposes of this section those terms are interchangeable.

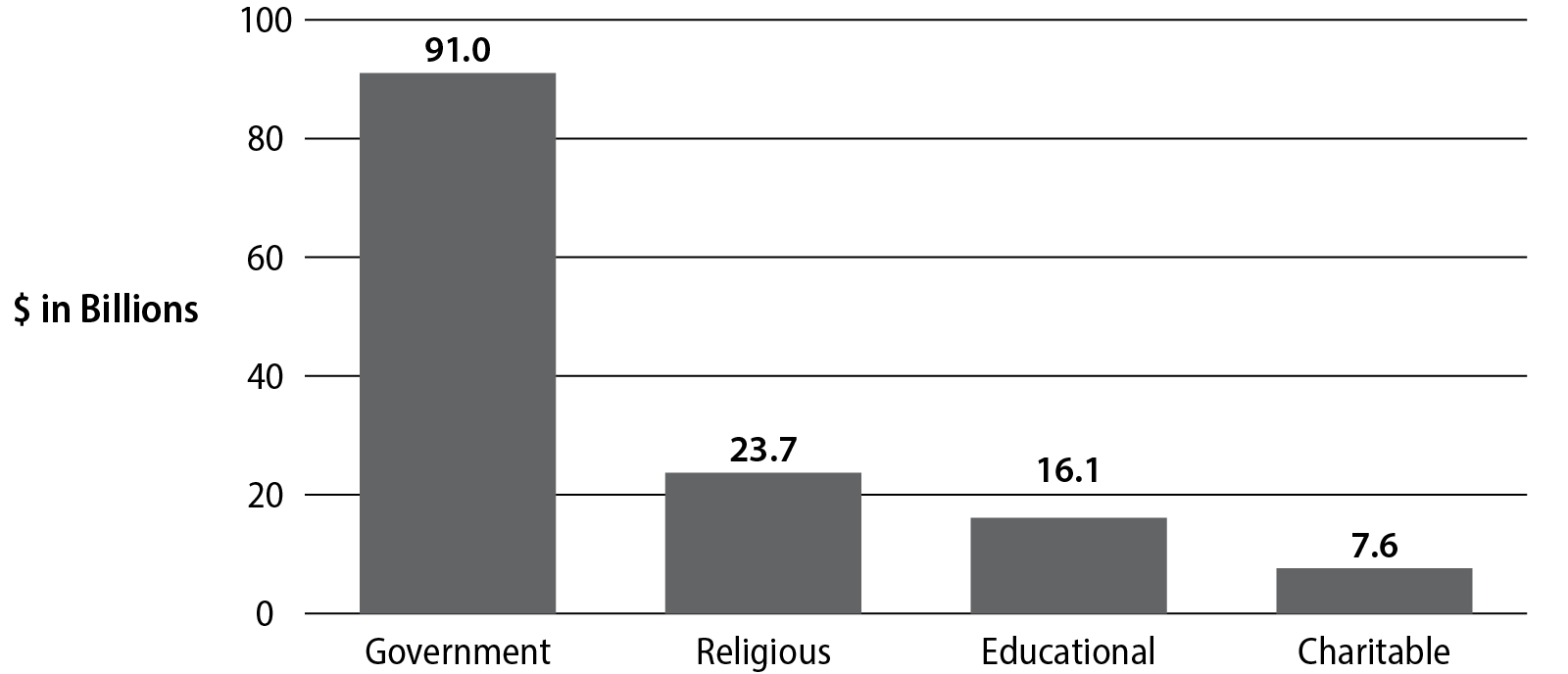

The single largest property tax exclusion category is present-use-value property. This exclusion, which applied to nearly $34 billion of property in 2021–2022, reduces the taxable value of land that is used for agricultural, forestry, or wildlife conservation purposes. Under this program, land owners are allowed to pay taxes on the value of their property at its value for its current use, as opposed to its actual market value for development or any other use. The taxes on the difference between the land’s present-use value and its market value are deferred, with the most recent three years of deferred taxes due and payable when the property is sold or is no longer used for agricultural, forestry, or wildlife conservation purposes. The next most-common exemptions are those for government, religious, charitable, and educational property. As Figure 5.4 illustrates, the largest of these four exemptions is the one for property owned by a government—federal, state, or local. Local governments have no authority to tax property owned by another branch of government, regardless of how that property is being used.

North Carolina Department of Revenue.

Three property tax exclusions are aimed specifically at elderly and disabled homeowners. The most popular of the three is the homestead exclusion, which reduces the taxable value of a residence by the greater of $25,000 or 50 percent. To be eligible, a homeowner must be 65 or older or totally disabled and must satisfy an income requirement, which was $33,800 or less for 2023. For example, if Tina Taxpayer is eligible for the elderly and disabled exclusion and her home is assessed at $200,000, she will pay taxes only on $100,000 of that value. Roughly $6.7 billion of residential property benefited from this exclusion in 2021–2022.

The other two exclusions are the disabled veterans exclusion (G.S. 105-277.1C), which allows qualified taxpayers to reduce the taxable value of their homes by $45,000, and the circuit-breaker deferred tax program (G.S. 105-277.1B), which permits senior homeowners to cap their current taxes at either 4 or 5 percent of their income. The circuit-breaker program is similar to the present-use value program in that three years of deferred circuit-breaker taxes are due when the taxpayer sells the home or stops using it as his or her primary residence. These two exclusions are much smaller than the homestead exclusion, especially the circuit breaker. In 2020–2021, the disabled veterans exclusion applied to $1.9 billion of property while the circuit breaker applied to less than $1 million.

Exemption and Exclusion Applications

The default rule is that a property owner must file an annual application to receive any exemption or exclusion.

Many exemptions require only a single application, including those for present-use value, educational, religious, and charitable property. Additional filings by the taxpayer are required only if an exempt taxpayer acquires additional property, makes physical changes to the exempt property, or changes its use of the exempt property.

A handful of exemptions, most importantly the one for government property, apply automatically without the need for an application from the property owner.

Applications for most exemptions and exclusions are due by the end of the listing period, which is January 31 unless the county commissioners decide to extend it. Applications for the three residential property relief programs—the elderly and disabled exclusion, the circuit-breaker exclusion, and the disabled veterans exclusion—are due on June 1.

Despite these deadlines, the Machinery Act permits governing boards to accept applications through December 31 for “good cause shown.” Because this term is not defined by the Machinery Act, governing boards have a good amount of discretion when deciding which late applications to consider. The only limitation courts have placed on this discretion is that local governments should not base their decisions solely on the amount of property taxes related to a particular application.

An assessor makes the initial determination on all exemption and exclusion applications. North Carolina courts have made clear that all exemptions and exclusions must be strictly construed in favor of taxation. In other words, assessors should begin with a presumption in favor of taxability. The burden of proof is on the taxpayer to prove that an exemption or exclusion is deserved. If the taxpayer disagrees with the assessor’s decision concerning an exemption or exclusion, the taxpayer may pursue an appeal to the county board of equalization and review and beyond, as described below.

Taxpayer Appeals

County commissioners play significant roles in resolving taxpayer appeals concerning their tax values and their eligibility for exemptions or exclusions, primarily through the appointment of the county board of equalization and review (BOER). The commissioners themselves may sit as the BOER or, as is most common, they may appoint other individuals to serve in that capacity.

Confusingly, the Machinery Act does not create a fixed deadline for taxpayers to submit appeals to the BOER. Instead, the appeal deadline is tied to the date that the BOER adjourns, which can vary from county to county and from year to year.

In non-reappraisal years, the BOER must adjourn by July 1. In reappraisal years, it must do so by December 1. But in practice, most counties adjourn their BOERs on the same day as or shortly after the BOER’s first meeting, which must occur between the first Monday in April and the first Monday in May. Once it adjourns, the BOER may still meet to hear appeals that were submitted before adjournment but cannot accept any new appeals.

Table 5.5 lists the five stages of a property tax appeal. Not surprisingly, most appeals occur in reappraisal years when every parcel of real property receives a new tax value. Historically, about 10 percent of real property owners contest their values after a reappraisal. The assessor usually resolves 90 percent of those initial inquiries informally.

|

1. Informal appeal to the assessor

2. County Board of Equalization and Review

3. State Property Tax Commission (taxpayer only)

4. N.C. Court of Appeals

5. N.C. Supreme Court (maybe)

|

Those appeals that are not resolved to the satisfaction of the taxpayer move to the BOER for formal hearings. The BOER’s decision is binding on the county, meaning that if the taxpayer prevails, the county has no right of appeal. However, if the county prevails, the taxpayer has the right to appeal to the North Carolina Property Tax Commission, a five-member panel that hears cases in Raleigh. The party that loses before the Property Tax Commission can appeal the case to the North Carolina Court of Appeals, which often is the final stop for property tax appeals. A losing party has the right to continue its appeal to the North Carolina Supreme Court only if at least one judge from the court of appeals voted in its favor. The supreme court may also exercise its discretion to hear the appeal of a unanimous decision from the court of appeals, but that rarely occurs.

Discoveries

A “discovery” occurs when an assessor learns of taxable property that has not been listed for property taxes. The term also applies when the value or volume of property was substantially understated or when a property has received an exemption or exclusion for which it did not qualify.

After a discovery is made, the assessor must correct the listing and assessment of the property and then bill the corrected taxes for the current year plus the five previous years. If the discovery involves personal property or buildings, discovery penalties of 10 percent per listing period apply to the discovery bill. Penalties do not apply to the failure to list land.

For example, assume that Billy BlueDevil builds a house on his vacant lot in 2016 but fails to list the building for taxation with the county. The county finally learns of the house’s existence in 2023. Under the discovery provisions, the county is entitled to list, assess, and bill that property for the current year (2023) plus the five previous years (2018–2022). Although the house should have been listed and taxed in 2017, the Machinery Act does not permit the county to extend its discovery bill back past 2018.

The discovery bill must be based on the assessed value and the tax rate in effect for each year the property was not listed. Table 5.6 shows how Billy BlueDevil’s discovery bill would be calculated, assuming that the house would have been assessed at $200,000 as of January 1, 2018, and that the county had not conducted a reappraisal since that date. The penalties are calculated at 10 percent per missed listing period for each tax year: for example, the 2018 penalty is 60 percent because Billy missed six listing periods (2018–2023).

|

Year

|

Assessed Value

|

Tax Rate

|

Tax

|

Penalty

|

Totals

|

|

2023

|

$200,000

|

.51

|

$1,020

|

$102 (10%)

|

$1,122

|

|

2022

|

$200,000

|

.51

|

$1,020

|

$204 (20%)

|

$1,224

|

|

2021

|

$200,000

|

.50

|

$1,000

|

$300 (30%)

|

$1,300

|

|

2020

|

$200,000

|

.52

|

$1,040

|

$416 (40%)

|

$1,456

|

|

2019

|

$200,000

|

.52

|

$1,040

|

$520 (50%)

|

$1,560

|

|

2018

|

$200,000

|

.50

|

$1,000

|

$600 (60%)

|

$1,600

|

|

Totals

|

|

|

$6,120

|

$2,142

|

$8,262

|

Waiving Discovery Bills

Local governing boards possess unusually broad authority over discovery bills. The Machinery Act permits discovery bills to be waived by a governing board at its unfettered discretion. The governing board may agree to waive the entire bill or just a portion of it. It could waive all penalties, the tax and penalties from certain years, or any combination thereof.

In comparison, regular tax bills, penalties, and interest generally cannot be waived by governing boards. See “Refunds and Releases,” below, for more details.

While the Machinery Act does not place any specific limits on the authority to waive discovery bills, governing boards are wise to seek consistency in their approaches to this issue. A lack of consistency when making waiver decisions could lead to accusations of favoritism or bias.

When a discovery bill includes municipal property taxes, that municipality’s governing board retains the authority to compromise that portion of the bill. The county commissioners may compromise only the portion of the discovery bill that involves county taxes.

Evaluating the Assessor

County commissioners can choose from a variety of metrics to evaluate the performance of their assessors. One major consideration is often the cost and effectiveness of the countywide reappraisal of real property. Reappraisals are usually the most controversial activity undertaken by a county’s tax office. To conduct a successful reappraisal, an assessor must possess technical appraisal skills, managerial competence, and perhaps above all, strong public relations capability. Educating taxpayers about the reappraisal and appeal process is a necessity, and the assessor cannot accomplish that key task without the ability to communicate clearly and effectively to different interest groups.

From a statistical perspective, the sales assessment ratio discussed earlier in this chapter may be the most useful figure for county commissioners to analyze. Immediately following a reappraisal, a county’s sales assessment figure should be very close to 100 percent, meaning that, on average, sales prices equal tax values. If that is not the case, the reappraisal was not very accurate and the assessor should be held accountable.

The assessor should not be held accountable for changes in the tax base due to economic conditions. The fact that tax values have not risen as much as the commissioners might have hoped or have not fallen as much as taxpayers might have expected does not mean that the assessor is incompetent. More often, it means that the observers’ expectations were not based on the actual conditions experienced by the county. Pre-reappraisal education is the key to minimizing unrealistic expectations on behalf of both elected officials and taxpayers.

Collection

After an assessor lists and assesses all taxable property in a jurisdiction and the jurisdiction’s governing board sets the tax rate, property taxes are handed over to the tax collector for billing and, if necessary, enforced collection efforts, such as bank account attachments, wage garnishments, and real property foreclosures.

As is true of the listing and assessing process, the collection process should normally proceed with minimal involvement by the governing board. The tax collector should apply the same collection procedures to all similarly situated taxpayers, free from political pressures.

The governing board’s role in the collection process is limited to

-

appointing a tax collector or, for municipalities, choosing to contract with the county for property tax collection;

-

deciding whether to offer taxpayers a discount for early payment; and

-

reviewing the tax collector’s performance throughout the year and after receiving the year-end settlement.

Appointing the Tax Collector

Every local government that levies property taxes must appoint a tax collector who will be authorized to use the Machinery Act collection remedies of attachment and garnishment, levy and sale, and foreclosure. That tax collector can be an employee of the taxing government or an employee of another government with whom the taxing government contracts for tax collection services.

The Machinery Act creates only a few limitations on who can be appointed as tax collector. Members of the governing board are ineligible to serve as tax collector, as are local government finance officers absent special approval from the Local Government Commission. In terms of education and experience, the only requirement is that the appointee be “a person of character and integrity whose experience in business and collection work is satisfactory to the governing body.” The appointee’s criminal and financial history must not be so bad as to prevent the local government from being able to purchase the required bond to cover losses caused by the tax collector’s misconduct or neglect. The bottom line is that the governing body has great discretion when deciding whom to appoint as tax collector.

The tax collector must be appointed for a set term determined by the governing board. Most commonly these terms are two or four years in length. Once fixed by the governing board upon the tax collector’s appointment, the length of the collector’s term may not be changed until the term ends or the collector is removed from office. No term limits exist for collectors, meaning the governing board may reappoint a particular tax collector repeatedly. After appointment, the tax collector can be removed from office only “for cause,” the same standard that is applied to the removal of the assessor.

Unlike assessors, tax collectors are not subject to mandatory state certification. However, the North Carolina Tax Collectors Association (NCTCA) operates a voluntary certification process for tax collectors. Many local governments now expect their collectors to obtain NCTCA certification as part of their required duties.

Tax Bills

Surprisingly, the Machinery Act does not require local governments that levy property taxes to send bills to their taxpayers. For obvious reasons, all do. But because tax bills are not required, a taxpayer cannot rely on failure to receive a tax bill as justification to avoid responsibility for a particular tax. The Machinery Act charges all taxpayers with notice of the fact that taxes are owed on their property even if they never receive actual notice in the form of a tax bill.

Tax bills cannot be created until the tax rate is adopted along with the budget for the new fiscal year. Local governments are expected to finalize their budgets before July 1, the beginning of the fiscal year. But this deadline is far from ironclad, and plenty of local governments delay the final budget decision well into the new fiscal year. Of course, the later the budget is adopted, the later tax bills will go out, and the longer the local government will wait to receive its property tax revenue.

Because the Machinery Act is silent on the issue of tax bills, local governments have flexibility as to the form and content of those bills. Any tax, fee, fine, or other obligation can be included on a property tax bill. But billing an obligation along with property taxes does not automatically empower the local government to use property tax collection remedies to collect that obligation.

For example, some local governments include water, sewer, or stormwater fees on their tax bills. Absent special approval from the state legislature, these fees cannot be collected using property tax collection remedies even though they are included on the same bill with property taxes.

An important exception to this rule concerns solid waste fees. All local governments are authorized to adopt a resolution calling for solid waste fees to be billed with property taxes and collected as property taxes.

Discounts for Early Payment

The Machinery Act permits but does not require local governments to offer taxpayers a discount for paying their property taxes before September 1, the due date for property taxes other than those on registered motor vehicles. Discounts are becoming less and less common. Those jurisdictions that do offer them usually set the discount at 1 or 2 percent. If a jurisdiction wishes to offer a discount, it must set the discount schedule by May and obtain approval from the N.C. Department of Revenue (NCDOR). Once adopted, a discount schedule remains in effect for all subsequent tax years unless and until it is repealed by the governing board.

Interest

Unlike discounts, interest is mandatory. On January 6 following the year in which taxes are levied, unpaid property taxes begin to accrue interest. For example, taxes levied for the 2023–2024 fiscal year become delinquent and begin to accrue interest on January 6, 2024. (Different rules apply to taxes to motor vehicles—see “Registered Motor Vehicles,” below.)

Interest accrues at a rate of 2 percent for the first month and 0.75 percent for every month thereafter. Machinery Act interest is simple interest rather than compound interest, meaning that interest does not accrue on interest. On the first day of each month that a delinquent tax remains unpaid, another 0.75 percent of interest accrues on the principal amount of taxes owed plus any penalties and costs that have been added to that amount. For example, tax collectors are permitted to apply a 10 percent penalty for checks returned by the bank for insufficient funds. That penalty is added to the principal amount of taxes owed and will accrue interest if it remains unpaid past the delinquency date.

Governing boards cannot waive interest charges unless that interest accrued illegally or due to clerical error. These are the same standards that apply to the release and refund of principal taxes. (See “Refunds and Releases,” below, for more details.)

Special Rules: Weekends, Holidays, and Postmarks

Two Machinery Act provisions affect when interest accrues in special situations.

The first is the weekend and holiday rule. Whenever the last day to pay a tax without additional interest falls on a weekend or holiday, the deadline is extended to the next business day. For example, January 6, 2019, fell on a Sunday, meaning that the last day to pay 2018–2019 property taxes without interest was a Saturday (January 5). The weekend and holiday rule extended this deadline to the next business day (Monday, January 7). Interest on unpaid 2018–2019 property taxes began to accrue on Tuesday, January 8.

The second is the postmark rule. The Machinery Act requires that tax offices treat property tax payments made by mail as if the payments were received on their postmark dates. Assume Tommy TarHeel pays his 2023–2024 property taxes in full by mail on Wednesday, January 3, 2024. The tax office does not receive his payment until Monday, January 8, several days after interest was to accrue on 2023–2024 property taxes. If Tommy’s payment has a U.S. Postal Service postmark date of January 4 or January 5, the tax office must treat the payment as if it were actually received on either date and no interest would accrue on Tommy’s property taxes. If the payment has no postmark or only a private postal meter mark, it cannot benefit from the postmark rule and Tommy must be charged interest.

Depending on the size of the locality, it may not be practical for tax office staff to check postmark dates on all payments made on or near an interest deadline. Instead, many tax offices apply a grace period of several days after each interest accrual date. Payments received by mail within the grace period do not accrue interest, without regard to postmark dates. While reasonable, tax offices should be aware that this practice satisfies only the spirit and not the letter of the postmark rule. Tax payments arriving after the grace period that have postmark dates prior to the interest accrual date should not be charged interest.

Deferred Taxes

Ten different Machinery Act provisions provide taxpayers tax relief in the form of deferred taxes. By far the largest of these deferred tax programs is the present-use value program discussed previously. But deferred taxes are also created under the circuit-breaker program as well as under exclusions that cover historic properties, working waterfront property, wildlife conservation land, and future sites for low-income housing.

Program details vary, but the general principle remains the same: some amount of taxes is deferred each year for as long as the property qualifies for the program. Interest accrues on these deferred taxes, but the local government cannot take action to collect them. When the property is sold or otherwise becomes ineligible for the program, several years (usually three) of deferred taxes plus interest become due and payable. If the deferred taxes are not paid immediately, the local government can proceed with enforced collection remedies.

Enforced Collection Remedies

Once taxes become delinquent on January 6, tax collectors can immediately begin enforced collections. The Machinery Act creates three enforced collection remedies: attachment and garnishment; levy and sale; and, for taxes that are liens on real property, foreclosure. Separate state provisions allow local governments to collect delinquent property taxes through the set-off debt collection process, which targets state income tax refunds and lottery winnings. All four remedies are summarized in Table 5.7.

Remedy

|

Property Targeted

|

|

Attachment and garnishment

|

Wages, bank accounts, rents, or any other money owed to the taxpayer

|

|

Levy and sale

|

Cars, boats, planes, or any other tangible personal property owned by the taxpayer

|

|

Foreclosure

|

Real property subject to a lien for delinquent taxes

|

|

Set-off debt collection

|

State income tax refunds, lottery winnings, or any other money owed to the taxpayer by the state

|

Local governments can also sue delinquent taxpayers in state court, but few pursue this option because the remedies available to a local government after winning such a lawsuit are essentially the same remedies it already possesses under the Machinery Act.

Unless the governing board directs otherwise, the tax collector normally may use any of these remedies in any order desired. However, once a foreclosure proceeding begins, all other Machinery Act remedies must stop.

Most local governments use all four tax collection remedies. But some refuse to employ collection remedies that taxpayers consider too intrusive, such as wage garnishment or foreclosure. Local governments that ignore any of these remedies suffer reduced collection percentages and lost revenues and do grievous harm to the perceived fairness of the property tax scheme.

Three of these remedies can be initiated without the involvement of the courts. Attachment and garnishment, levy and sale, and set-off debt collection require only notice to the taxpayer and, in the case of attachment and garnishment, notice to the party that holds the property being attached.

A court proceeding is required for foreclosure, which is available only for taxes that are a lien on real property. All taxes on real property automatically become a lien on that real property on the listing date, which is the January 1 prior to the fiscal year for which the taxes are levied. The tax lien on real property also includes the taxes owed on personal property other than registered motor vehicles that is owned by the same taxpayer in the same jurisdiction.

For example, assume that Wanda Wolfpack owns real property Parcel A, a boat, and a registered Honda Civic, all of which are listed for taxes in Carolina County. The taxes on both Parcel A and the boat are a lien on Parcel A. The county could foreclose on Parcel A for Wanda’s failure to pay either the taxes on the real property itself or the taxes on the boat. The taxes on the Honda Civic are not a lien on Parcel A, meaning that the tax collector could not foreclose on Parcel A if Wanda failed to pay the taxes on her Civic.

The Machinery Act creates a ten-year statute of limitations for all enforced collections. Foreclosures, attachments and garnishments, and levies must begin within ten years of the delinquent tax’s original due date, which for all taxes other than those on registered motor vehicles is September 1 of the year the taxes were levied.

Who Can Be Targeted with Enforced Collection Remedies?

Only property of the responsible taxpayer can be targeted with enforced collection remedies. G.S. 105-365.1 creates different rules for the responsible taxpayer for taxes on personal property as compared to real property. For personal property, the responsible party is the taxpayer that listed the property for taxation, meaning the owner on the previous January 1. In other words, new owners of personal property are not responsible for old taxes on that property. For real property, the responsible parties are the owners as of the date of delinquency (January 6 of the fiscal year) and all subsequent owners. In other words, new owners of real property are responsible for old taxes on that property. Table 5.8 summarizes the rules concerning responsible taxpayers.

Type of Property

|

Original Owner

|

Subsequent Owners

|

|

Real property

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Personal property (boats, planes, business property)

|

Yes

|

No, unless “going out of business” provision applies

|

|

Registered motor vehicles

|

Yes

|

No

|

Here is how the rules work for real property. Assume that Dave Deacon owns Parcel A, on which taxes from 2022–2023 are delinquent. He sells Parcel A to Susie Seahawk in June of 2023. Normally, Susie (or her attorney) would require that the delinquent taxes be paid at or before the closing. But if those taxes are not paid, Susie would be personally responsible for the old taxes on Parcel A despite the fact that the taxes became delinquent while the property was owned by Dave (on January 6, 2023). Dave would also remain personally responsible. To collect these taxes, the tax collector could foreclose on Parcel A, garnish Dave’s or Susie’s wages, attach Dave’s or Susie’s bank account, or seize and sell Dave’s or Susie’s car or other personal property. If Susie’s cash or property is taken to satisfy the taxes, Susie may have a legal action against Dave for reimbursement. But that depends on the terms of the real estate contract between Susie and Dave and has no effect on the taxing unit’s right to collect the delinquent taxes using all methods permitted by the Machinery Act.

Now consider a personal property example. Assume that Mike Mountaineer owns a boat on which 2022 property taxes are delinquent. If Mike sells the boat to Wanda Wolfpack, Mike remains the only party personally responsible for the 2022 taxes on the boat. Only Mike’s wages, bank accounts, and other property may be targeted with enforced collections. The tax collector cannot seize and sell the boat or target any of Wanda’s other property because responsibility for taxes on that boat does not transfer to its new owner.

Although multiple collection actions are permitted for a single delinquent tax, that tax may be collected only once. For example, in the real property example above, the tax collector could simultaneously pursue wage garnishments against both Dave and Susie for the delinquent 2022–2023 taxes on Parcel A. In the personal property example, the tax collector could simultaneously attach Mike’s wages and bank account for the delinquent 2022 taxes on the boat. Tax collectors are permitted to proceed with multiple collection actions for delinquent taxes simultaneously. But once the full amount of delinquent taxes plus interest and costs are collected, all collection actions must stop and any excess funds collected must be returned to the targeted taxpayer(s).

Property Taxes and the Register of Deeds

About three-quarters of North Carolina’s 100 counties have received authorization from the General Assembly under G.S. 161-31 to prohibit a register of deeds from accepting a deed transferring real property unless the county tax collector first certifies that there are no property tax liens on the property that is the subject of the deed. This certification must cover all property taxes that the tax collector is responsible for collecting, which could include county taxes, municipal taxes, special service-district taxes, rural fire-district taxes, and supplemental school-district taxes. This provision provides great incentive for a closing attorney to ensure that the taxes on property being transferred are paid because, otherwise, the deed cannot be recorded, and the buyer’s ownership rights may be jeopardized. Unfortunately, the provision contains a loophole that permits attorneys to record deeds if they promise to pay the delinquent taxes at closing. Too often these promises are broken and the taxes remain unpaid after the deeds are recorded.

G.S. 161-31 lists the counties with the authority to enact this requirement. If a county is not on that list and desires this authority, it should ask its state representatives to introduce legislation adding it to that list. Although the statute covers municipal taxes only if those taxes are collected by the county, at least one municipality that collects its own taxes has obtained a local modification to the law that prohibits the recording of deeds unless municipal taxes are paid along with county taxes.

Advertising Tax Liens

Despite increasing questions about their effectiveness, newspaper advertisements of delinquent real property tax liens are still required every year. The cost of these advertisements can be substantial, with larger counties spending tens of thousands of dollars to buy newspaper space. Tax collectors are permitted to pass these costs along to the delinquent taxpayers, and much of the advertising cost will be recaptured when the delinquent taxes are paid. But because not all of these taxes will be paid, the local government is certain to wind up eating a portion of the advertising cost.

Due to cost and to administrative burden, some local governments have considered eliminating tax lien advertisements. This course of action is not recommended for two reasons.

First, the advertisement is the mandatory initial step for an in rem foreclosure, the Machinery Act’s expedited foreclosure process that can be accomplished without the need for attorneys. If a tax collector were to move forward with an in rem foreclosure without first advertising the tax lien, the taxpayer would have strong grounds for defending or reversing that collection action.

Second, local governments that do not use the in rem foreclosure process could place their other collection actions at risk if they intentionally ignore the advertising requirement. While the Machinery Act and state courts are generally tolerant of good faith errors in the tax collection process (see the discussion under “Immaterial Irregularities—Recapturing Lost Taxes” below), they are less likely to be forgiving of willful illegality by a local government.

Evaluating the Tax Collector: The Tax Collection Percentage

The Machinery Act requires tax collectors to make monthly reports to their governing boards about their collection results. These reports, combined with the annual settlement required of tax collectors summing up their efforts and results for the entire fiscal year, give governing boards multiple opportunities to evaluate the performance of their collectors.

Perhaps the most important statistic used in the evaluation process is the tax collection percentage. Thanks to the very effective collection remedies provided by the Machinery Act, county collection percentages are very high, averaging around 99 percent for the past few years. Collections of taxes on registered motor vehicles traditionally lagged behind collections of other property taxes but have increased substantially since the 2013 implementation of the Tag & Tax Together collection system described below.

Two factors that can affect an individual local government’s collection percentage are property tax assessment appeals and bankruptcies, both of which prevent a tax collector from pursuing enforced collections against the taxpayer in question. If a jurisdiction experiences either a high number of property tax appeals during a reappraisal year or a bankruptcy filing by a major commercial taxpayer, the tax collector will not be able to collect the taxes involved while the proceedings are pending. As a result, the collection percentage is likely to suffer.

“Settlement” is the term the Machinery Act uses for the required annual accounting that tax collectors must provide to their local governing boards. Presented after the old fiscal year ends and before the tax collector is charged with taxes for the new fiscal year, the settlement accounts for all of the funds received by the tax collector and identifies those taxes that remain unpaid. The settlement must be provided to the board in written form, but most tax collectors also make an oral presentation to the governing board so that they can answer questions in person.

As part of the settlement, the tax collector will usually provide the governing board with tax collection rates, often times broken out by year or property type.

Although collection percentage is the most common and usually the most important criterion used to evaluate a tax collector, other aspects of the collector’s performance can and should be considered by the local governing board. The collector’s ability to communicate with the board and with the public is key to an effective property tax system. Taxpayer complaints and the collector’s responsiveness to those complaints are related issues that may provide insight into that official’s performance.

Consistency and impartiality are vital characteristics for a tax collector. The board needs proof that the collector demonstrates these traits. Does the tax collector treat all similarly situated taxpayers equally? Does he or she employ tax collection remedies in an impartial fashion against all delinquent taxpayers and not play favorites? If not, the local government is likely to face taxpayer dissatisfaction and legal exposure.

Old Taxes

The Machinery Act creates a ten-year statute of limitations that bars enforced collection actions after taxes are more than ten years past due. Most counties rely on this statute of limitations to allow their tax collectors to write off taxes after they hit the ten-year mark. Technically, this approach violates the Machinery Act. The statute of limitations bars enforced collection, but it has no relevance to the tax collector’s responsibility for those taxes.

The only technically correct method of writing off taxes and thereby relieving tax collectors of responsibility for them is through the “insolvents list.” As part of the settlement process, a tax collector should identify unpaid taxes from the just-ended fiscal year that are not a lien on real property. The governing board can then place those taxes on the insolvents list and, once those taxes are more than five years past due, can write off those taxes by relieving the tax collector of responsibility for them. Taxes on registered motor vehicles that are placed on the insolvents list can be written off after they are more than one year past due.

Note that taxes that are a lien on real property cannot be placed on the insolvents list and, therefore, technically can never be written off by the tax collector. When all other efforts fail, foreclosure remains an option for any tax that is secured by a lien on real property. The problem, however, is that property that makes it through to a foreclosure sale is often worth very little. It may be more effort than it is worth to pursue foreclosure, which is why many counties allow the tax collector to informally write off old taxes on real property despite the Machinery Act’s contrary admonition.

Immaterial Irregularities—Recapturing Lost Taxes

From a local government perspective, few Machinery Act provisions are more beneficial than the “immaterial irregularity” provision. Essentially, this provision excuses errors in the listing, assessing, billing, and collecting processes and allows local governments to retroactively correct those errors and levy and collect the taxes in question as if the errors never occurred.

Cities and counties have relied on the immaterial irregularity provision in a variety of situations. They have used it to retroactively bill taxes on property that was listed by the taxpayer but never assessed, to pursue taxes on property that was annexed by a municipality years ago but never taxed by it, and to collect underbillings resulting from computer errors.

About the only type of error that courts have found significant enough not to be excused is the failure to give adequate notice to owners of real property before moving forward with a foreclosure action. Local governments using the foreclosure process should take care to provide timely notice to all parties who may have an interest in the property being foreclosed upon, including lien holders and the heirs of deceased taxpayers.

Refunds and Releases