Chapter 9

Internal Control in Financial Management

by Rebecca Badgett

Introduction

Local governments have a duty to be good stewards of public moneys and assets. To accomplish this, units must take measures to safeguard moneys and assets and ensure that they are used for authorized and lawful purposes. Chapter 8 discusses the statutory internal controls mandated by the Local Government Budget and Fiscal Control Act (LGBFCA) that relate to depositing, investing, obligating, and disbursing public funds. This chapter explores a step-by-step process that local units can use to design and implement a strong system of internal control over financial-management operations, recognizing that each internal control system should be uniquely tailored to each local unit’s needs and capabilities.

Establishing a Framework of Internal Control

There are two widely accepted frameworks of internal control on which a local government may choose to base its internal control system. The first is the Internal Control–Integrated Framework, issued by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). COSO is a voluntary organization dedicated to improving the quality of financial reporting and strengthening internal control in private-sector organizations. The second framework is the Government Accountability Office’s Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, known as the “Green Book.” The Green Book is the legally required internal control framework for federal entities, but it may be adopted by other public-sector organizations, including state and local governments, quasi-governmental agencies, and not-for-profit organizations.

The guidance and approach to internal control offered in the Green Book and in the COSO Internal Control–Integrated Framework are similar. Both frameworks structure the approach to internal control by using five key components that are supported by seventeen underlying principles. While either framework may form the basis of a local government’s internal control system, this chapter summarizes the guidance stipulated in the Green Book because the Green Book model is intended for use by public-sector organizations, including local governments.

Internal Control Defined

The Green Book defines internal control as a “process effected by an entity’s oversight body, management, and other personnel that provides reasonable assurance that the objectives of an entity will be achieved.” An entity’s objectives should be classified under one or more of the following categories:

-

Operations—Effectiveness and efficiency of operations

-

Reporting—Reliability of reporting for internal and external use

-

Compliance—Compliance with applicable laws and regulations

This definition highlights a few key points. First, internal control is a process; it is not one event but is, rather, a series of actions that will prove to be most effective when operationalized into daily business operations. This process must be consistently monitored, evaluated, and updated to ensure that it is functioning at the optimal level. Second, even the strongest internal control system provides only reasonable assurance that a unit’s objectives will be met. Absolute assurance is not possible due to the inherent limitations of internal control, such as unintentional mistakes and errors, management override of established controls, and external factors like natural disasters, cybersecurity breaches, a pandemic, or other events outside of a unit’s control. Lastly, the underlying objective of internal control is to safeguard public moneys and assets from loss. A local unit must design its control system to limit opportunities for fraud and must put controls in place that prevent or promptly detect mistakes, errors, and acts of fraud by employees.

Responsibility for Internal Control

The Green Book’s definition of internal control places responsibility for internal control on “management” and the “oversight body.” A third category, “personnel,” includes employees who assist management with the implementation of controls and must report any functional issues to management.

Management

Management is responsible for the design and implementation of a unit’s internal control system. The term “management” generally includes persons in upper-management positions such as the senior finance officer(s), the county or municipal manager, department heads, and possibly the unit’s attorney. Although the auditor may suggest changes to improve the effectiveness of established controls, the unit’s auditor is not responsible for implementing internal controls and should not be included in the internal control “management” team.

Management should keep in mind that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to internal control. Every unit’s internal control system should be tailored to meet the unique needs and capabilities of the unit. It is helpful to consider factors such as size, organizational structure, operating style, number of personnel, or other special circumstances that may impact the overall function of the control system. For example, in small units, the manager may play a key role in carrying out certain responsibilities that a manager in a larger unit is not expected to perform. Small units also face certain challenges, such as having limited staff, which can make it difficult to ensure adequate segregation of duties.

Oversight Body

The oversight body is responsible for overseeing management’s design and implementation of the unit’s internal control system. In local government, the elected governing board is by default the acting oversight body. The governing board may appoint a separate committee to act as the oversight body if the full board does not want to assume oversight responsibility. In such instances, the appointed oversight committee may include a mix of governing board members and senior management. In small units, the oversight body may need to take a more active role in the internal control process by helping management design effective controls or by compelling compliance by instituting and enforcing meaningful consequences for noncompliance.

Components of Internal Control

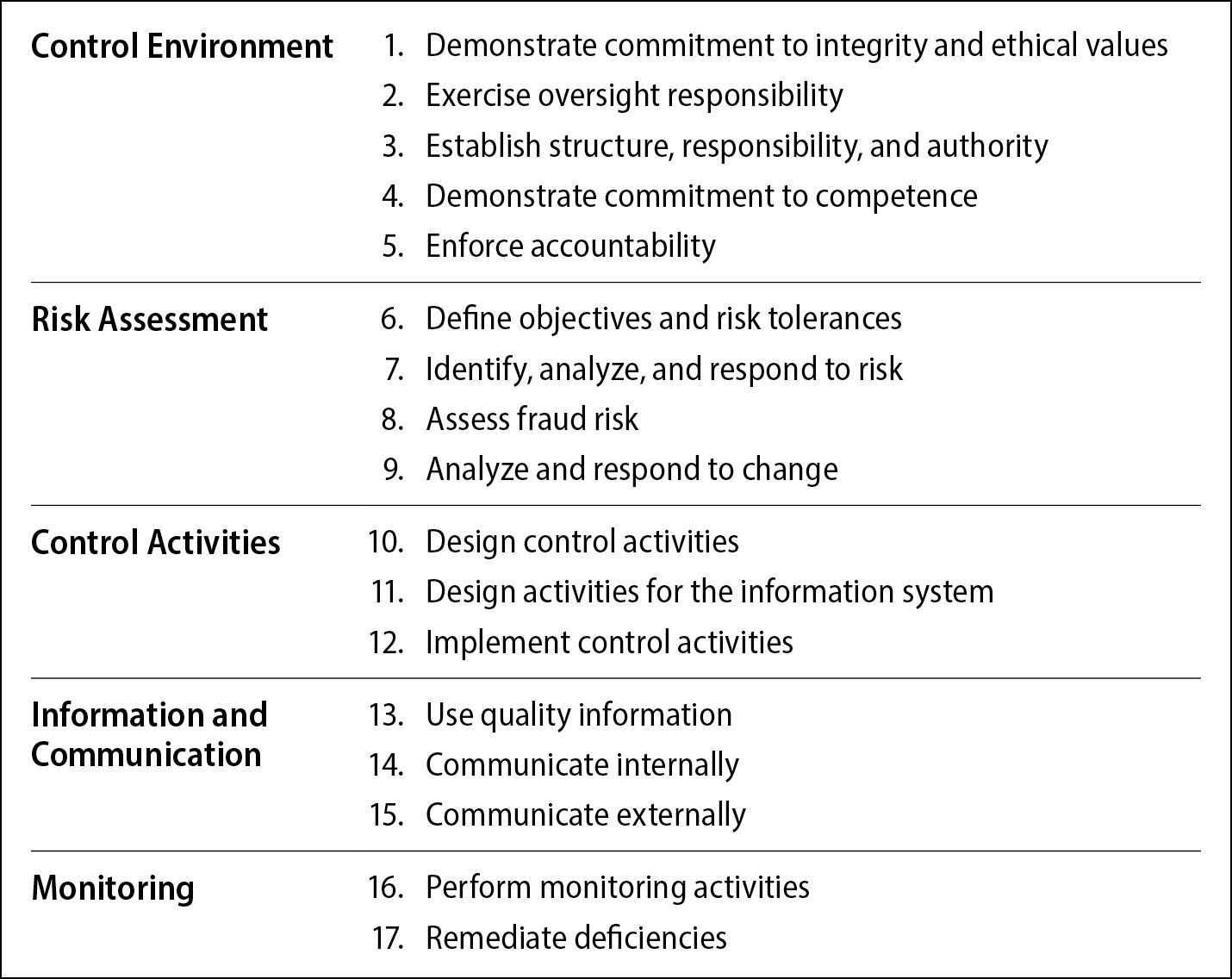

The Green Book approaches internal control through a hierarchical structure of five components and seventeen principles (see Figure 9.1). The five components of internal control are:

-

control environment,

-

risk assessment,

-

control activities,

-

information and communication, and

-

monitoring.

The seventeen principles explain the requirements necessary to implement the associated components. In general, every component and principle is necessary and should be operationalized to help establish the most effective internal control system.

1. Control Environment

The first component of the Green Book’s internal control framework is control environment. This component serves as the foundation of the internal control system. It is sometimes called the “tone at the top” or, in the private sector, “corporate culture.” A strong control environment is fostered when management and the governing board communicate to employees the importance of ethical behavior and competence in the workplace and the need to follow established internal control processes. The principles that support the control environment, set out in the paragraphs below and identified by their number in the Green Book’s listing (see Figure 9.1), can serve as a road map to help create a strong control environment.

-

The Oversight Body and Management Should Demonstrate a Commitment to Integrity and Ethical Values (Green Book Principle 1). To satisfy this principle, the local unit’s oversight body and management should adopt a code of conduct to communicate expectations concerning integrity and ethical values. Management may rely on the code to help evaluate the attitudes and behaviors of employees and departments and to determine the tolerance level for deviations.

-

The Oversight Body Should Oversee the Unit’s Internal Control System (Green Book Principle 2). To satisfy this principle, the oversight body must oversee management’s design, implementation, and operation of the internal control system. The oversight body should test controls and consider whether the current internal control system is adequate to mitigate risks and guard against potential acts of fraud. The oversight body may provide guidance and offer suggestions on how to remediate any apparent weaknesses or deficiencies in the internal control system.

-

Management Should Establish an Organizational Structure, Assign Responsibility, and Delegate Authority to Achieve the Unit’s Objectives (Green Book Principle 3). To satisfy this principle, management will want to (a) consider how the departments within the unit interact to fulfill the unit’s overall responsibility and (b) establish clear reporting lines with the unit’s organizational structure. Organizational charts are helpful in establishing reporting lines. For example, an organizational chart for the finance department could illustrate the reporting lines and level of authority between the various finance-related positions, such as the finance officer, deputy finance officer, accountant, payroll specialist, treasurer, and other positions. When advertising a new finance position, the position description should match the level of authority designated in the organizational chart. Management can use the organizational chart to delegate internal control responsibilities to personnel down the reporting chain of command.

-

Management Should Demonstrate a Commitment to Recruit, Develop, and Retain Competent Employees (Green Book Principle 4). Management must recruit and hire qualified personnel to fill vacant positions and provide current employees with training opportunities to help ensure that the employees maintain the level of competence necessary to accomplish assigned responsibilities. This requires management to have a clear understanding of job duties and position responsibilities.

-

Management Should Evaluate Performance and Hold Individuals Accountable for Their Internal Control Responsibilities (Green Book Principle 5). To satisfy this principle, periodic performance reviews should be conducted to evaluate whether employees are competent and performing assigned internal control responsibilities. For example, if the unit has a policy that requires the deputy finance officer to attach the preaudit certificate to contracts or purchase orders, management should review whether the employee is in fact meeting this expectation. Disciplinary action may be taken when instances of noncompliance are identified.

2. Risk Assessment

The second key component of internal control is risk assessment. Risk assessment is a process undertaken by management to identify risks facing the unit as it seeks to achieve its objectives. Conducting a risk assessment allows management to identify areas in need of control activities. The goal of the risk assessment is not to eliminate all risks facing the unit, as this would be impossible. Instead, management should determine an acceptable level of risk and consider how to keep risk factors within agreed-upon confines. Management should strive to identify internal and external risks that may affect unit-wide operations, department operations, and process- or activity-level operations. It can be effective to approach the risk assessment as a three-step process:

Step 1: Management defines operational, reporting, and compliance objectives.

Step 2: Management identifies risks related to achieving the identified objectives.

Step 3: Management assesses the risks based on likelihood and impact to determine a response.

Step 1: Identify Objectives (Green Book Principle 6). Management within the finance department should begin the risk assessment by identifying objectives related to general financial operations and for each significant transaction cycle, such as budgeting, cash receivables, accounts receivable, accounts payable, capital assets, debt, and investments.

There are three categories of objectives that management should strive to identify: operational objectives (what must happen to ensure that business operations are running efficiently?); reporting objectives (what must happen to ensure that financial statements, budgets, and other financial records are accurate and timely?); and compliance objectives (what must happen to ensure compliance with the LGBFCA and other governing federal, state, or local laws?). The more specific the objectives, the easier it will be for management to identify risks to achieving those objectives in the next step. Examples of objectives related to a unit’s financial process include the following:

-

Financial reports that include updated budget-to-actual revenues and expenditures should be prepared and presented to the governing board monthly.

-

Cash receipts are accurately recorded in the Daily Collection Report.

-

Accounts receivables are accurately credited to the correct user account.

-

A preaudit is performed as required by law and the preaudit certificate is attached to each contract or agreement that obligates the unit to expend public moneys.

-

Access to the payroll system is restricted to authorized users.

-

All journals, ledgers, and other accounting records are reconciled as part of the month-end closeout procedure.

Step 2: Identify Risks (Green Book Principle 7). During the second step of the risk-assessment process, management should take steps to identify the risks that, should they occur, may negatively impact the unit’s ability to achieve its objectives. It is important to understand the different types of risk and the internal and external factors that can impact those risks.

Inherent risk. Some transactions or operations are by their nature inherently risky. For example, the acceptance of cash payments always carries with it an inherent risk of loss, as cash can easily be stolen or misappropriated. This is also true for transactions involving the storage or exchange of personal property such as laptop computers and other electronic equipment. In addition, risk generally increases when the unit undertakes new or complex programs or activities, such as the administration of a new federal grant award. For example, under the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, every municipality and county in North Carolina was eligible to receive distributions of federal financial assistance (i.e., a federal grant award) from the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund (CSLFRF). The acceptance of CSLFRF funds obligated local government recipients to administer the award in compliance with the U.S. Department of Treasury CSLFRF Award Terms and Conditions and other Treasury regulations and guidance. Due to the complexity of the CSLFRF award’s compliance and reporting requirements, there is an inherent risk of error or noncompliance, whether intentional or not.

Change risk. Any change in business operations or personnel may increase risk. For example, the use of new technology or software is an operational change risk. The hiring of new employees or the retirement of a long-term employee may also increase risk—new hires must overcome a learning curve associated with every new position, and institutional knowledge can be lost when an employee retires or leaves.

Fraud risk. Management must always consider where there may be opportunities for an employee to commit fraud against the unit. There are three primary types of fraud to look for during the risk assessment: (1) corruption (e.g., bribery, bid rigging, or collusion); (2) asset misappropriation (e.g., embezzlement, lapping, and other fraudulent disbursement schemes); and (3) fraudulent financial reporting, which involves the intentional misstatement or the omission of amounts in financial statements or accounting records with the intent to deceive the financial statement user.

The following questions may serve as a starting point to help management identify areas of risk within financial operations.

-

Are finance employees qualified and trained to perform basic accounting functions and to create and maintain financial reports?

-

Are unit policies and procedures properly documented and updated to reflect current practices?

-

Does the unit have budget violations in its audit findings?

-

Is the unit current with its audits? If not, why?

-

How could accounting errors occur and remain undetected?

-

Which assets are most liquid and prone to theft?

-

If an unauthorized purchase is made, how will it be detected?

-

Could a payment be made for goods or services before it is verified that the goods or services were received?

-

Are bank accounts and financial records regularly reconciled?

-

Are passwords/IT system-access controls sufficient to protect unauthorized access to electronic records and databases?

-

Is there a process to ensure that employees who leave no longer have electronic access to records or databases?

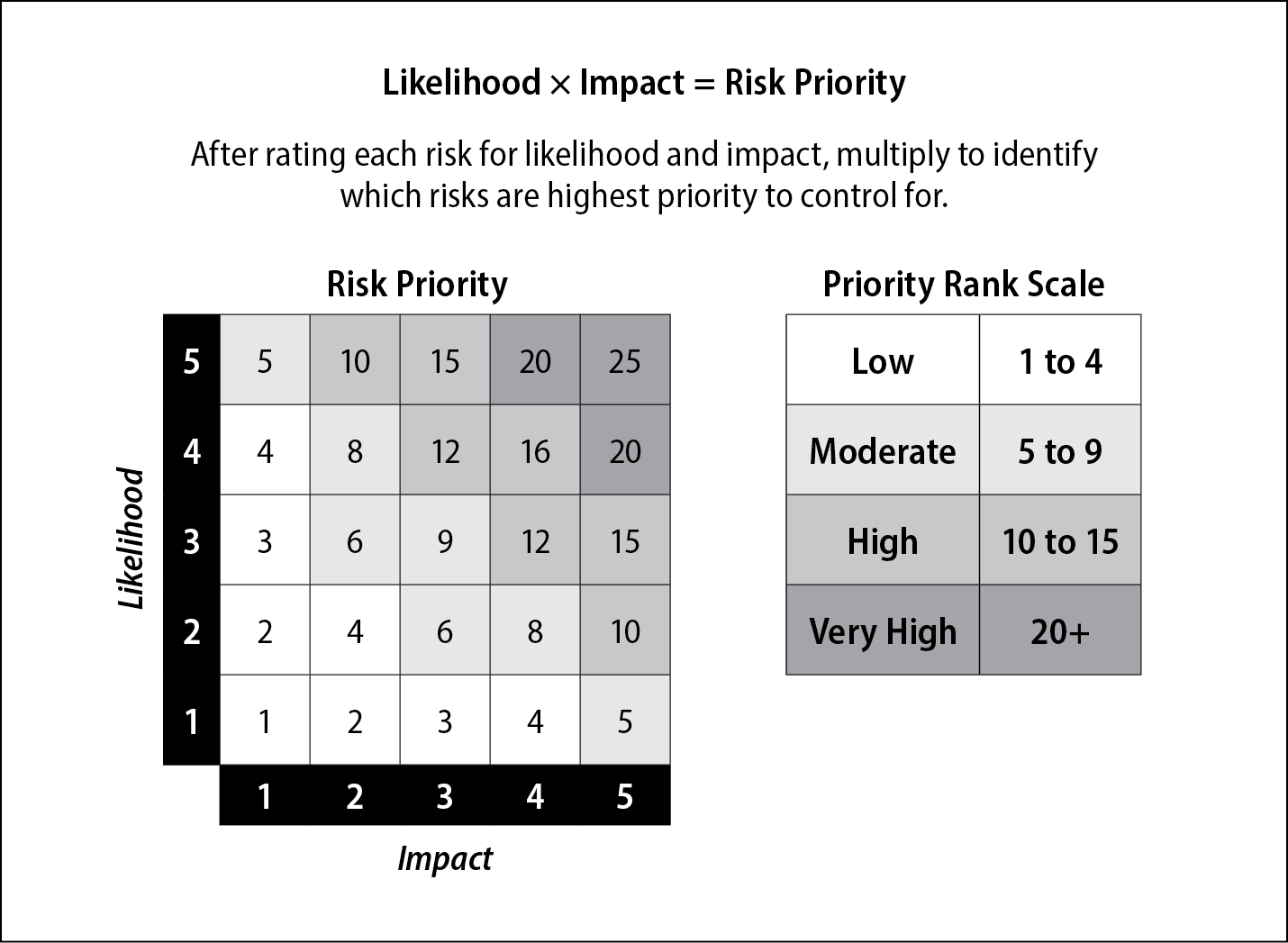

Step 3: Assess Risk and Determine a Response (Green Book Principles 8 and 9). Once a local unit’s management has identified risks, it must decide how to respond. Not all risks are created equal. Some risks may be so remote, or the effects of such risks so inconsequential, that the unit may decide simply to accept those risks without developing controls to address them. Some risks, like natural disasters, may have such significant negative impacts that, even if unlikely, the unit must limit the risk through the purchase of insurance. For all other risks, management can implement control activities to help reduce the likelihood or impact of identified risks.

To help determine which risks should be limited through control activities, management should evaluate each risk using a likelihood/impact scale to determine priority (see Figure 9.2). Those risks that rank “very high” or “high” on the unit’s risk-priority scale should be reduced through the implementation of control activities. Management must weigh the cost (time, money, effort) of implementing a control activity with the resulting benefit, keeping in mind that the cost of mitigating the risk should not exceed the cost to the unit if the risk occurred.

3. Control Activities

The third key component of the Green Book’s internal control framework involves control activities. Control activities are the processes, procedures, and techniques designed by a unit’s management team to help provide reasonable assurances that the unit’s objectives will be met. Control activities are generally either preventative or detective. Preventive controls are designed to deter the occurrence of an undesirable event, while detective controls help identity when an undesirable event has occurred. In addition to reducing identified risks, all control activities should promote an effective and efficient workplace. It is important to note that control activities can stand alone or be used in combination with other measures. Green Book Principle 10 addresses how to design control activities; Principle 12 covers the implementation of these activities. The following list describes some of the most common control activities.

-

Written policies and procedures. Written policies and procedures are a key internal control activity. These written tools can be used to communicate behavioral expectations, establish workflow processes, and define internal control responsibilities. Policies and procedures help operationalize control activities, and written procedures should be used to describe all major financial transaction cycles, such as accounts receivable, accounts payable, payroll, investments, cash receipts, and capital assets. A strong control environment is fostered when management requires written policies and procedures that are communicated, followed, and regularly updated to reflect current business processes.

-

Authorization and approval. The establishment of clear authorization and approval authority helps facilitate smooth workflow processes and ensure that financial transactions are lawful and consistent with a local unit’s objectives. “Authorization” involves a delegation of authority to an employee granting that employee the right to perform a specific task or responsibility. For example, a purchasing officer may be authorized to make small purchases without supervisory approval. “Approval” is the confirmation of an event or transaction based on an independent review by an employee with approval authority. Approval indicates that the approver has reviewed supporting documentation and has verified that the transaction is accurate and complies with applicable laws and regulations. For example, a department head may approve a purchase order, indicating that the purchase is necessary and lawful.

-

Segregation of incompatible duties. Segregation of incompatible duties is often described as implementing a system of checks and balances. This control is beneficial because it minimizes the risk that a single employee will be able to commit fraud or conceal errors. Segregation of incompatible duties involves separating job duties so that no one employee can (1) authorize a transaction, (2) record the transaction in the accounting records, (3) maintain custody of the asset resulting from that transaction, and (4) reconcile records that reflect the transaction. For example, if a unit’s purchasing department plans to purchase ten new laptop computers, a supervisor could authorize the purchase via a purchase order, another employee should pay the invoice and record the transaction in the unit’s accounting records, a third employee should verify the receipt of the computers and maintain custody of the assets, and a fourth employee should reconcile accounting records to ensure that the transaction has been accurately recorded. In small units, full segregation of incompatible duties may not be practical due to limited staff and overlapping job duties. In that case, it is recommended that a minimum of at least two employees complete any transaction. The same employee should not be responsible for both the recording and reconciliation functions. Small units should adopt compensating controls to ensure extra review of the unit’s financial transactions.

-

Compensating controls. When adequate segregation of duties is not possible, a local unit should adopt compensating controls. Compensating controls involve the additional review of financial records and transactions by someone in management or by a governing board member. For example, if only two employees handle the accounts payable process, a governing board member, an internal auditor, or a member of senior management can review accounting records, bank statements, and financial reports to ensure that the accounts payable transactions are accurate, and that fraud is not going undetected. In some instances, two small units may decide to “swap” reconciliation duties to ensure an independent review of financial transactions when there is limited capacity.

-

Documentation. Management must ensure that employees create and retain written documentation that evidences all financial transactions and facilitates the budgeting, financial reporting, and audit processes. Financial records, reports, and supporting documentation should be easily identified and be readily available to the governing board and to any auditor with whom the unit has contracted to perform auditing services.

-

Reconciliation. Account reconciliation is used to verify the accuracy of financial records through the periodic comparison of source documents and accounting records. Account reconciliations should be performed regularly, ideally after each month-end closeout. A local unit should not wait until the end of a fiscal year to reconcile its accounting records or rely on the auditor to perform reconciliations.

-

Physical controls. Physical controls include the steps taken to protect real and personal property, including IT equipment, cash, checks, supplies, materials, and any other type of tangible asset from the risk of loss, misappropriation, or misuse. Physical controls include physical barriers, such as storing cash and valuables in locked cash boxes or safes, storing electronic equipment in locked storage rooms, or restricting access to public buildings and facilities to authorized employees.

-

Information-system controls (Green Book Principle 11). Information-system controls facilitate the proper operation of information systems and help ensure the validity, completeness, accuracy, and confidentiality of transactions. Management is responsible for designing the unit’s information system to respond to the unit’s objectives and risks. The information system includes both manual and technology-related information processes. General system-access controls facilitate the proper operation of the information system and include security management and access controls, such as requiring dual authentication to access certain electronic records or databases. This is a complex control area, and management should ensure that it has adequately addressed threats of cyber attacks and other issues that may result from insufficient cybersecurity controls.

-

Education and training. Management has a duty to hire and retain competent personnel who have the proper education and training to perform job duties effectively. To ensure that employees have the necessary skills and training, employees should be allowed, or in some cases required, to attend supplemental training, conferences, or other educational events to advance skillsets and learn new competencies.

The fourth key component of internal control under the Green Book framework is information and communication. While sometimes overlooked, this component is essential to the creation of a strong internal control system. A local government’s management team should establish communication channels within the unit (Green Book Principle 14; Principle 15 deals with external communications) that provide timely and accurate information and updates (Principle 13 states that quality information should be used); inform employees of their internal control duties and responsibilities; allow employees to suggest ways to improve the system’s operation; and convey a commitment by management and the unit’s oversight body to the adherence of established internal control processes. These communication channels can take many forms and may include emails, meetings, casual conversations, or training on how to perform specific internal control activities. Management may want to periodically verify that communication channels are effective and that employees are receiving and sharing information as intended.

5. Monitoring

Monitoring is the fifth and final key component of internal control. Effective monitoring of a unit’s internal control system allows management to determine whether policies, procedures, and other control activities designed and implemented by management are being conducted effectively by employees. When monitoring techniques are built into the unit’s business operations (Green Book Principle 16), control deficiencies may be more readily identified and corrected in a timely manner. Management is not required to review every transaction or financial report to determine whether controls are properly functioning. Instead, management can spot-check transactions, financial reports, and account reconciliations for timely completion and accuracy. For example, management can spot-check paid invoices to determine if the goods or services covered by the invoices were certified as having been received prior to authorizing payment. Management can monitor whether employees are properly segregating incompatible duties and performing other control activities as assigned. It may be helpful for management to solicit feedback from those employees responsible for carrying out the control activities in the unit to help determine if they are effective. Efforts should be made to document the performance of monitoring activities. If a breakdown in the system is identified, management may change the design of the controls to improve the operating effectiveness of the system (Principle 17 involves remediating deficiencies).

Internal Control over Federal Awards

As a condition of receiving a federal award, a non-federal entity, including a local government recipient and any subrecipients, must agree to maintain a system of internal control over the federal award that provides reasonable assurance of compliance with applicable laws and regulations and with the terms and conditions of the award. A non-federal entity’s internal control system should be modeled after the guidance offered in the Green Book or after the Internal Control-Integrated Framework issued by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). Accordingly, a non-federal entity should use the five key components and seventeen principles of internal control outlined in the Green Book, and discussed herein, as the basis for the design and implementation of its internal control system over federal awards.

When it comes to managing the financial aspects of federal awards, non-federal entities must design and implement strong and robust systems of internal control. These controls should help ensure compliance with the financial management standards set forth in 2 C.F.R. § 200.302. These standards require, among other things, that non-federal entities retain records that adequately identify the source and application of award funds. In addition, non-federal entities must create and retain accounting records that adequately track authorizations, obligations, unobligated balances, assets, expenditures, income and interest, and these records must be supported by source documentation.

Any non-federal entity that expends $750,000 or more in federal awards during a fiscal year must undergo a federal single audit. As part of the single audit, the auditor will test the effectiveness of the non-federal entity’s internal controls over the federal award. The Office of Management and Budget’s annual Compliance Supplement is a resource intended for auditors, but it is also a helpful tool for non-federal entities that have triggered a single audit. The Compliance Supplement includes a Matrix of Compliance Requirements for each major federal program that indicates which of the twelve compliance requirements the auditor will test during the single audit. Part 6 of the Compliance Supplement includes two appendixes that provide illustrative examples of internal control—Appendix I contains examples of entity-wide controls over federal awards, and Appendix II provides examples of internal controls specific to each compliance requirement. These appendixes can serve as a starting point as the non-federal entity starts to design and implement internal controls over federal awards.

Summary

A strong internal control system is necessary to help ensure that the unit is operating at the optimal level and will achieve its goals and objectives. Properly designed and functioning controls over key financial transactions and processes will significantly reduce the likelihood that errors or fraud will occur and remain undetected. When a local unit’s management team and governing board take time to implement the internal control framework outlined in the Green Book, they are signaling to all unit employees and to external stakeholders that the unit values internal control and has taken the steps required to be a good steward of public moneys and assets.